Published in:

Germany’s biggest nature travel magazine

14 pages | text & photography

“Never wander around the cave without a light! There can be holes or abysses up to a hundred metres deep practically everywhere”, British speleologist Howard Limbert warns us. I am sitting in the safety briefing on the premises of Oxalis, the licensee and thus the only organiser of expeditions into Son Doong Cave.

Located in the Phong Nha-Ke Bang National Park in central Vietnam, “Mountain-River Cave” is considered the largest cave in the world.

Seated next to me are nine other expedition members, including an American landscape photographer, an Australian oil worker and a Thai YouTube star. Howard warns us: “Be sure to keep your feet dry. Rub talcum powder on them every night or you’ll get this.”

He shows us pictures of feet with unsavoury skin diseases that look like something out of a horror movie. Afterwards, we talk about the dangers of snake bites, abrasions and falls, and then two hours later we all shuffle back to our accommodation a little intimidated.

The next morning the Oxalis site is bustling with activity. The entire expedition team has assembled here: ten members, twenty porters, five photo assistants, two British speleologists, a Vietnamese cave guide, two cooks, two national park rangers and the head of the of the porters. The latter supervises the distribution of the tents, food for five days, clothing, climbing equipment, cooking utensils, medicines and much more.

The porters stuff everything into countless green plastic backpacks, until they can hardly be lifted anymore. I look at the shoulder straps of the backpacks which are only two fingers wide and I am glad not to be one of the porters for the next five days.

After a one-hour bus ride, the entire team is dropped off at the starting point. We put on our backpacks and march along a path that runs steadily downhill. After about an hour, we cross the Rao Thuong River for the first time.

Our cave guide Ian “Watto” Watson, a 62-year-old Briton, loudly warns us in the broadest of Yorkshire slang: “Don’t even think about wringing out your socks. It takes far too much time. In two minutes we will have to go through the same river again anyway.”

Most of us are wearing special canyoning boots from which the water drains away. I, on the other hand, have opted for cross-country shoes – not a very good idea as it turns out. Next to the laces I see in tiny print “Gore Tex”. It means that the river water will stay in my shoes, and a rhythmic squelching accompanies me all day. Involuntarily I see the horrible images of disfigured feet from the night before. I hope everything goes well!

The tents appear like colourful Lego bricks in the mouth of a gigantic stone monster.

After a while we pass the tiny village of Ban Doong with a population of just 35 to 40 inhabitants. I smile at a girl and point to my camera. She smiles back and nods.

For another two hours we continue on upstream in the now mercilessly stinging sun and we cross the river countless times more. Everything below the navel is and remains dripping wet. Suddenly the river disappears into in a huge rock wall. Watto turns to us: “Welcome to Hang En Cave! The porters will move on ahead and prepare our camp a little further on. Tomorrow we will march to the exit to reach Son Doong.”

We take a short break and put on our caving equipment: a helmet with a strong lamp and robust gloves to protect us from the razor-sharp rock edges. Through huge boulders we move slowly upwards into the cave. This is what ants must feel like. I look down from an elevated position on our camp for the night: the tents down there look like colourful Lego bricks in the mouth of a gigantic stone monster.

Half an hour later we reach camp. Some of us take a dip and cool down in the water and let dozens of gala fish nibble off skin. Above us thousands and thousands of swifts are twittering. On their mobile kitchen the Vietnamese cooking crew prepares a variety of delicacies of sticky rice, fresh vegetables, omelette and pork for dinner. “You definitely won’t lose weight here,” Watto laughs.

Early the next morning we set off to cross the Hang En cave, and after about an hour we reach the monumental cave exit. Then three more hours of walking along and in the river, as well as some climbing through the dense jungle. We take a break to recharge ourselves and eat muesli and chocolate bars and put on our climbing gear before we start the last stretch up to the Son Doong cave.

After a strenuous passage we finally stand in awe before a steaming gullet of rock and stone: the entrance to Son Doong Cave. Cold air deep from within the bowels of the earth meets the heat of the day and condenses into vapour. This is exactly where the Vietnamese Ho Khanh stood in 1990, as he sought shelter from a tropical downpour.

He climbed a few metres into the cave until it became too steep and slippery. Ho Khanh is considered to be the discoverer of the cave, but at that time he had no idea of its enormous dimensions.

After several unsuccessful attempts, he only managed to find the entrance again in 2008. He then confided in Howard Limbert, who a year later put together an expedition that explored the cave for the first time.

Howard recalls: “At the time we went in, we had no idea that we were dealing with the largest cave in the world.” It was like being a climber and finding a new Mount Everest. That was an absolute highlight for us spelunkers!”

One of the rare moments when I’m not carrying the camera. I’ve just given it to the porter walking in front of me, because otherwise it would probably have bumped against the rocks. And the person carrying it takes a picture right away, of course. By the way, the gloves protect me from the sharp stones.

Directly behind the cave entrance, the path goes steeply downhill. We abseil 80 metres into the darkness, then cross chest-deep underground rivers and climb over sharp rocks.

Again and again suddenly appearing “steam baths” that obscure our view: underground clouds! Anette, our young Vietnamese cave guide, explains: “The Son Doong cave has its own climate because it is so big. There are several openings in the cave roof so that the air can circulate and create winds.”

My headlamp illuminates the path in front of my feet quite well, but when I look up towards the cave’s ceiling, the light disappears into a void.

The record-breaking dimensions of the cave can only be seen in the extremely powerful cave lamps that the expedition assistants are now setting up. The Son Doong Cave, with its maximum dimensions of 200 metres high, 145 metres wide and 5 kilometres long, is the largest cave passage in the world. This volume is equivalent to 139 times the Empire State Building.

There are no paths, stairs or similar amenities in the Son Doong Cave. Every step, every grip must be taken with utmost care. Anyone who stumbles, slips or falls, can fall very deep and suffer sprains or fractures.

Even minor wounds are very unpleasant, as they hardly heal due to the permanent humidity. I deeply admire our Vietnamese porters who, with their man-sized heavy backpacks and wearing only plastic sandals on their feet, are jumping past me, singing, joking and smoking cigarettes.

Suddenly a light shimmers in the distance: a sinkhole, a natural shaft of light. Over millions of years, the underground river has carved a tunnel through the rock. In the process, the rock cover became thinner and thinner and eventually collapsed. We set up our second night’s camp in front of the doline. I am grateful to be able to enjoy daylight in the cave.

After breakfast we fight our way through huge boulders for an hour, always towards the light of the doline. Before our eyes stretches a vast green expanse, bordered by steep, slippery walls all around. The rock stretches 200 metres vertically up to the opening of the doline.

I trudge past plants, bushes and trees up to 30 metres high. This cave jungle is unique in the world, explains Watto, a delicious cocktail of humidity, bat droppings and daylight allowed this very special ecosystem to sprout. That is why my Yorkshire spelunker buddies have named this doline “Watch out for dinosaurs”.

There have already been more people on the summit of Mount Everest than in the depths of this cave

Having reached the opposite end, we descend again into the darkness of the cave. Hours later we come within sight of the second sinkhole. Three assistants lead the way with the powerful cave lamps to sufficiently illuminate our subject, the entrance to the second sinkhole.

Until the lamps have been positioned it takes a quarter of an hour, which we use as a welcome breather. For me these small breaks are also important to be able to remind myself again and again at what a special place I find myself at the moment. I want to savour every moment here – after all more people have been to the top of Mount Everest than in the depths of this cave.

After leaving the second doline behind us, we set up camp for the third night, recharge ourselves with a delicious dinner and then climb even deeper into the cave until we reach a chamber of about 400 metres long. It is so big that this time it takes six people to illuminate it completely.

I set up my tripod and want to clean the camera, but I can’t find a dry fibre on my body. From the waist down to my shoes everything is soaked by the water from the river, and my upper body drenched from sweat up to under my helmet.

Tim, an American photographer, trips over a stone while walking back and has an unfortunate fall on his camera. “Shit!”, he curses and scowls at his demolished Nikon and the smashed wide-angle lens. Luckily he has a second camera with him.

The Son Doong cave hike is not for the unathletic or timid. Again and again we have to rope up, abseil down or cross rivers in which we sink in up to our chests.

We cross the chamber and arrive at a lake. “Hey, how lucky we are!”, Watto rejoices. “Normally we’d have to struggle through knee-deep mud here, but the rain of the past weeks has not yet run off. I can now invite you on a little paddle tour!”

The first of us let the cave lamps shine brightly and board the boats that the Oxalis crew has stored here. From my vantage point I can see 600 metres into the distance to the end of Son Doong Cave. It is truly breathtaking!

Then I also board a boat and paddle to the far end of the lake. Here, at the end of the cave, the 200-metre high, slippery “Great Wall of Vietnam” rises out of the water. In order to get to the exit of the cave, we would have to climb the wall and then trudge through thick mud. As this would definitely be too dangerous and very exhausting, my “cave mates” and I humbly refrain from doing it.

A few of us rise to the occasion instead, we remove our gear and jump into the wonderfully cool, crystal-clear water, I too, rinse myself of sweat, dust and sand before we set off on the one-and-a-half-day hike back to the cave entrance.

Only when we dare do we feel the value of life

Back home in Berlin, I reflect on my caving adventure in Vietnam. I ask myself: Why would one expose oneself to such risks and dangers? I find my personal answer to this through another question: When do we long for home, for our homeland?

Not when we are sitting on the sofa or in the garden, but whenever we are exposed to the unknown. It is only from a distance that we become aware of the value home has for us – and that can conjure up strong emotions. It is not just by accident that we speak of being homesick.

It is the same with taking adventures and risks. That which is not possible in the rigid corset of everyday life can be lived out on journeys, in personal adventures.

The experiences gained, enriched with a good pinch of risk, have a unique character. They are powerful, uplifting and unforgettable stormy waves in the otherwise usually rather calm river of our personal journey. Or to summarize, it is only in daring that we feel the value of life.

Read now:

Pure inspiration

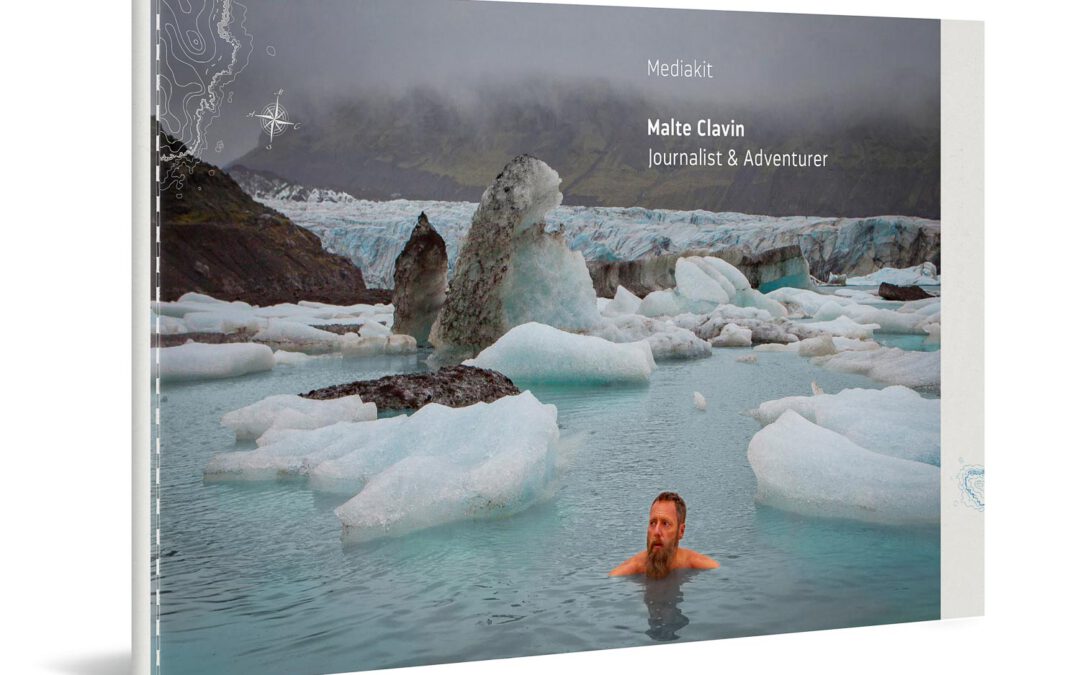

My new media kit 2025

< 1 Min.In this brand new 28-page media kit, I show you my work as an adventure journalist and speaker: Expeditions, travels, challenges – everything that excites me. Let yourself be inspired.

Son Doong Cave Expedition

Vietnam photo gallery

< 1 Min.I can’t say it any other way: this was the most awesome thing I’ve ever done: The five-day expedition through one of the largest caves in the world in Vietnam. I couldn’t forget the amazement and sweating.