Published in:

Germany’s biggest nature travel magazine

12 pages | text & photographs

can hardly believe what I see on the screen of my smartphone: The drone continues to rise above the river, then above the treetops. Now I am directly looking at immense, steep rock faces: the Table Mountains! They are barely visible from the river, the trees on the edge of the river obscure the view. Thanks to the drone that I launched from the boat a few minutes earlier, I can now see the brown defiant walls for the first time to their full extent, which I cannot gauge. The mesas must be several kilometres across.

I am still staring spellbound like a little child at the tiny screen.

If the sight of the tepuis, as the mesas are also called, doesn’t take your breath away, you are beyond help. They rise steeply up out of the endless jungle to almost a kilometre high. At the top, on the edge of the summit plateau, are isolated turrets, craggy crevices and eroded clumps of rock, in which clouds seem to get caught and wrap around.

I am still staring spellbound like a little child at the tiny screen, forgetting everything around me. And then this thought comes over me: this is the most beautiful landscape I have ever seen.

View over the fascinating landscape of Canaima National Park. Ayuan Tepui in the background.

Suddenly there is a beeping and a whining: the battery is running low. I tell Ben, my guide. He asks me: “Can you see the sandbank in your display?” I tell him yes. “You can land there. We’ll moor the boat there.”

How fortunate! A short while later I hear the familiar hum of my drone, and it is already about 20 metres above the boat. I move the control levers down, it’s supposed to land. No reaction. The drone continues to hover above us.

Then suddenly an alarm signal, which I haven’t heard before. The display shows blue waves. Someone shouts: “You have sunken your drone into the river! Suddenly I realise that the drone hovering up there is not mine at all! At the time of my take-off, a Venezuelan man was also letting his aerial vehicle into the air. That’s the one I’m looking at right now.

The boatsman and his aide jump into the water, dive after my drone. After about a minute, the boatsman triumphantly holds my dripping drone into the air! I can’t believe it. The drone has to be repaired, but the most important thing: the pictures are saved!

Within a few minutes we are soaking wet from the spray.

Behind the waterfall

Just the day before, the Venezuela adventure began. From Caracas, I flew with a few fellow travellers in a propeller plane to Canaima National Park.

Shortly after landing, we marvelled at the foaming waterfall Salto Sapo. A hollow behind the thundering masses of water allowed us to explore it from behind. Within a few minutes we are soaking wet from the spray – which no one minds with temperatures of around thirty degrees.

Behind the Salto Sapo waterfall.

Up next is a long boat ride to our first hammock accommodation. Early next morning we continue upstream by open boat. No sign of civilisation – as if we were the very first ones to visit.

Kingfishers and macaws flit sporadically along the riverbank. Then I launch the drone – and only now get a glimpse of where we are.

The Kerepakupai Merú River that we are on, runs like a light blue vein through a vast verdant sea of jungle, with table mountains rising majestically at the end. No wonder this landscape has always enraptured and inspired creative minds.

Arthur Conan Doyle, who became famous for Sherlock Holmes, published the novel ‘The Lost World’ in 1912. In it, a population of dinosaurs survived on the Table Mountain plateaus, which in turn inspired Steven Spielberg to make his film ‘Jurassic Park’.

And James Cameron, who made Avatar, the most successful movie ever, was so enthusiastic about Venezuela that he incorporated many landscape elements in the home planet of the Na’vi people.

After dinner, we fall wearily into our hammocks.

Highest of its kind

Finally, a first view of the Salto Angel, at 979 metres the highest waterfall in the world. The country’s most famous natural attraction bears the name of the American pilot Jimmie Angel, who first sighted it in 1933.

The boat moors on the shore. Then it is a walk of a few hundred metres in altitude until we can admire the waterfall from a sloping rock. Although the Salto Angel now only carries about 20% of its normal water mass in the dry season, no one here is unimpressed.

Shortly before dark, we cross over to the other side of the river. There we rinse off the sweat and sand in the shallow river water. After dinner, we fall wearily into our hammocks.

The rock faces of Mount Roraima just ahead.

A moment you can’t buy

The day dawns. I slip out of my hammock and trudge to the riverbank. No sound of civilisation can be heard, only the murmur of the river, rain dripping from trees, parrots squawking in the distance.

Salto Angel is completely shrouded in a thick blanket of clouds. A few minutes later, the first rays of sunlight break through the cloud cover and reveal the view of Salto Angel.

A flashing turquoise blue morpho butterfly flutters by. Joachim turns up next to me. Silently we beam at each other and take in this moment that no amount of money can buy. It is a view for the gods.

A fourteen hours drive is ahead of us, fifteen times we have to stop at police and military checkpoints.

On the road again

Puerto Ordaz. The day begins at 5 am. The seven-seat off-road vehicle takes its seven passengers plus luggage. Since there is not enough room for everything on the roof, we also have to pack stuff inside. It gets narrow and I have the opportunity to test my claustrophobic limits anew.

We head straight south to the starting point of the hike up Mount Roraima, the largest of the 115 mesas. What we do not anticipate: a fourteen hours drive is ahead of us, fifteen times we have to stop at police and military checkpoints. Why so many checkpoints?

Many Venezuelans earn extra money by selling petrol.

It is said that the uniformed officers cannot make ends meet with an income of far less than 100 dollars per month. So they have to earn some extra money, e.g. by fining the owners of the dilapidated, barely roadworthy vehicles of most Venezuelans.

Official tourist vehicles like ours, with a permit and a seal from the ministry, are allowed to pass without any problems.

We overtake an endless queue of cars, in between tables where men are playing dominoes. I count about 300 vehicles.Their destination: a petrol station. Those who queue here wait many hours, some up to five days.

Petrol is subsidised by the government, sixty litres cost about one dollar. On the black market, no one has to wait, but they have to pay 25 cents per litre.

This route is notorious among truck drivers.

Driver Isaias is calm and level-headed personified. He knows the route inside out. “We used to speed through here at 120 km/h, now I have to slow down every few hundred metres and carefully drive through potholes.

Especially in the rainy season, it can get treacherous: The potholes fill up with water and are then no longer recognisable.”

It is slowly getting dark, the road climbs, becomes more curvy. “Now it gets interesting.” reveals Isaias with a slightly nervous undertone and throws in a fresh piece of chewing gum.

A few minutes later, rusted and dented sea containers appear in the headlights to the right and left of the road. This route is notorious among truck drivers: sharp bends in the road.

Children of the village of Paraltepuy. In the background the two tepuis: Kukenán on the left, Roraima on the right.

By now it is pitch dark, we are crossing the Gran Sabana, translated as the great steppe, a huge plateau. No lights far and wide. We are on the road in the fourteenth hour. Then, finally, lights on the horizon: our destination San Francisco de Yuruani is approaching.

Twenty minutes later, the seven of us are feasting on our hostess Magda’s meal. She has cooked rice, meat and vegetables. A local speciality is served for seasoning: pickled ants’ abdomen.

Boulders rumble against the bottom of the jeep.

On to Table Mountain

The next morning we continue our journey: twenty kilometres of off-road track to the last village before the Table Mountains: Paraltepuy.

On the way up flat termite mounds litter the landscape. Giant grasshoppers crouch on long blades of grass. When they fly, the fiery red undersides of their wings flash out. Boulders rumble against the bottom of the jeep.

Isaiah’s face remains calm. The path is so steep and slippery in places that everybody but for Isaias has to get out so that the jeep can come through.

Arriving in Paraltepuy, we get our first view of Mount Roraima. It seems close enough to touch. But it will take more than two days of hiking before we reach its steep rock faces.

A giant grasshopper on the way to the starting point of the hike to Mount Roraima.

Ornithologist and guide Leo Zamora introduces us to the terrain. He points to the slightly closer mesa on the left: “That’s the Kukenán Tepui, also called Matawi,” he says, “Matawi in the local language means Kamaracoto: you will die.”

He turns his head and stares at us deadly serious. Then he bursts out in laughter: “Haha! Don’t worry, it won’t happen.”

I divide my luggage up into several drybags. My porter Walter distributes these into his traditional guayáre, an open, handmade bast basket that must be ancient. The other three porters from the village also all use a guayáre.

A 14 km march is scheduled. The path is easy, flat, not to be missed. Everyone walks at his or her own pace, just continuing on towards the Roraima. But it hardly seems to be getting any closer.

We don’t have lunch until around 5 pm. The guides and porters are pressing hard, they want to reach the night camp before dark.

The current is very strong at places, each step is to be taken with care.

The sun sets and we cross the first river. The water is up to our knees. Only minutes further on, the second river, wider, louder, more powerful.

The porters are looking for a suitable place to cross, a little nervousness is written all over their faces. My porter Walter instructs me to unbuckle my photo belt and wear it on my shoulders – otherwise everything could get wet.

I am advised to keep my socks on, they offer more grip on the slippery stones than bare feet.

By now it is dark. The current is very strong at places, each step is to be taken with care. Walking sticks provide additional support. Having reached the other bank, everything below our bellybuttons is wet. We get dry in the tent camp, only two minutes away.

Ascent day to Mount Roraima – balance and stamina are required.

Further uphill

After a refreshing morning swim in the river, the one we crossed the night before, we set off. The trail climbs up.

We watch birds hunting insects. They are Fork-tailed Kingbirds, easily recognised by their distinctive long tail feathers. Organbirds and hummingbirds flit by so quickly that we can’t get a closer look at them.

However, over the next few hours, we can easily spot pygmy sparrows, grey-bellied shadow hummingbirds, groove-billed ants and crested caracaras. A little caution is advised when a rattlesnake crosses the path.

The weather is completely unpredictable.

The Gran Sabana used to be a jungle. Much of it has been burnt down, even the Indians set fires to make it easier to hunt tapirs and deer.

The weather is completely unpredictable. Clouds come up again and again and then it rains. As soon as the clouds lift and open up views of the table mountains, it becomes magical. This also applies to the neighbouring Tepui of Roraima, the Kukenán. It is home to Venezuela’s second highest waterfall at 674 metres. The scenery on the summit of the Kukenán once served as inspiration for the animated film Up from 2009.

Tropical Kingbird, Tyrannus melancolicus.

During a break, I photograph Jaime, one of our local guides and porters. It is one of the rare moments when I can sense his exhaustion. Jaime is wearing Crocs and cotton clothes. His guayáre is filled with a 35 kilograms load. Jaime is completely soaked. Not a word of suffering, a curse or an expression of regret escapes his mouth. That impresses me.

When we arrive at the next night’s campsite, he and his comrades are already there. They welcome us with friendly smiles and warm tea. We strengthen ourselves with the meal that chef Daniele prepares for us.

Any fall could end up with broken bones.

Ascent day

Bird lover Leo is beside himself: “44 endemic bird species exist in Venezuela, half of them here, around Roraima. With a bit of luck, I can spot one or two of them”. To do this, he has a bird-call app on his smartphone, the sounds of which he can play through a small loudspeaker to attract fellow species. And it works! A Giant Olivaceous Flycatcher approaches and sticks its head up towards the loudspeaker.

Now, on the day of the ascent, the path becomes much steeper, muddier and rockier. More branches and trunks block the way. Strength, fitness and balance are required. Any fall could end up with broken bones. A vulture hawk hovers far above us.

A natural pool on top of Roraima.

Finally we reach Roraima. It feels like giants built a colossal city wall. Thick drops fall on us down from the plateau of Roraima. Clouds race over its edge. On we go. Ever steeper, ever muddier.

Then a key section, the sight of which gives us palpitations: a steep section of the path leads directly under the impact zone of a waterfall. The lower part is dispersed by the wind, so that the waterfall has the effect of a strong rain shower. Leo warns: “Be very careful when climbing up. You can easily trigger rocks that could hit those behind you.”

We made it! Almost, anyway.

I mount through the passage with all due attentiveness. These are the very places I love so much: wild, untamed, difficult to reach. Therein lies their special magic.

A little further up, I turn again to look at that key section, now a rainbow circles the waterfall with two of my fellow travellers.

We have to struggle for another three quarters of an hour until we finally reach the top after a total ascent of six hours. We made it! Almost, anyway. We have not yet reached our camp for the night. We marvel at the uneven, primeval-looking landscape. I wouldn’t be at all surprised if one of the dinosaurs described in ‘The Lost World’ would come trotting around the corner.

Roraima: The clouds are constantly changing, visibility is sometimes only a few metres.

While we look around in amazement, Isaias keeps trying to make contact by radio with the team that went ahead, which is now preparing the camp for the night. But where are these fellows? Isaias’ radio messages remain unanswered. We have no choice but to search all possible shelters one after the other. The next hour we head for three possible campsites, but without success. Slowly it gets dark, the fog thickens, the temperature drops.

Finally, a crackle on the radio, the familiar voice of Gabriel, the head of the vanguard, comes through. Twenty minutes later we reach the ‘hotel’, as Isaias calls it: a row of five tents, squeezed tightly together under a rain-protected rocky outcrop.

80 % of all organisms are endemic here.

A world of its own

Here, at 2,800 metres above sea level, we are lucky with the sunny weather; it can rain for a week at a stretch. Ideal conditions now for exploring the plateau, even though we will only see a fraction of the 40 square kilometre area.

80 % of all organisms are endemic here, i.e. they only exist here on Roraima, nowhere else in the world. Besides many flowers, blossoms and peculiar plants, this also includes the small, black Roraima frog, which we are now marvelling at.

The endemic tiny Roraima frog: Oreophrynella quelchii.

Can you imagine that we are looking at two billion old rocks here?”, Leo asks me. I shake my head. Leo continues, “If nature were to shoot a time-lapse of the formation of Roraima, we humans wouldn’t even be visible, so insignificant is our past history compared to this eternity.”

Pensively I leap on, from rock to rock, some crevasses are pitch black, I couldn’t imagine what would happen if I fell into them. Sometimes I jolt up briefly when I step into water. The water is so calm and clear that puddles are not recognisable as such.

Only a moment later, everything turns into a dense soup of fog again.

The cloud formations change constantly, at times visibility is only a few metres. Then, within seconds, it clears out again and the sun beams down. Only a moment later, everything turns into a dense soup of fog again.

Relaxation in the eco-lodge

It took almost two days of driving, and now I arrive at the Casa Maria Lodge of Gaby and Norbert Flauger. It is called ‘Bug’s Paradise’. Owner Norbert is a great bug lover, he gained a lot of experience in large bug breeding in Berlin.

On the approximately 5-hectare site, many secluded corners invite you to linger. In one part, you can marvel at 15 aquariums. Even the floor seems alive: many of the tiles are decorated with handmade animal reliefs. A reading corner beckons with a hammock. On it rests a caligo, a butterfly with a large eye spot on the underside of its wings.

A man with countless talents and passions: Norbert Flauger. Here at his 3D slide projector.

In the garden, with a little patience, you can spot squirrels, butterflies, monkeys and sloths. Large insects buzz around. No, they are hummingbirds! Hungrily they flit from one flower to the next. I try unsuccessfully to catch them with my camera.

I take a break in a hammock in the reforested grove next to the lodge. Before I do, I scare up a few frogs. A centipede crawls over a branch. A bird makes an exotic metallic sound. My soundtrack for a little reading time. I have landed in paradise.

I tell him about my fruitless hummingbird photo hunt.

In the evening, Norbert tells me about the solar house he has built nearby. I tell him about my fruitless hummingbird photo hunt. He laughs: “Why didn’t you ask me? I know a lot about hummingbirds. I wrote a book about them. I have hung drinking containers for the hummingbirds on the terrace of the solar house. You can photograph them there easily. But you will need four flash units, one from each side, and a special power supply unit that supplies the flash units with power. Do you have that?” I say no. I want to try it anyway.

We set off the next morning, reach the hidden stone house with the solar panels and I marvel at ten containers of nutrient solution. Hummingbirds are constantly suckling on them. I lie in wait and press the shutter about 1,000 times over the next few hours. Two weeks later, at home, I gather out the successful shots: there are four.

Many different hummingbird species feast on this nutrient solution.

I am the only guest at Casa Maria, but I never feel lonely. Not only do at least 15 wall masks from all over the world watch me dine in the open dining room, but the lovely Gaby takes care of my well-being and with Norbert I have settled into the perfect division of roles: I ask, he answers.

„You have to go into nature to find a solution.“

A peacock calls from the garden. Then other birds, all of which Norbert recognises by their song and immediately tells me their Latin name. “About 140 species of birds have been observed in our garden, over 300 in the immediate vicinity.” he reports.

This man is a walking encyclopaedia. From Norbert I learn that some animals can produce light without generating heat, a principle that engineers have not yet fully understood. Stick insects can lift extreme weights, they make optimal use of the laws of lever, highly interesting for robot engineers. Norbert sums up: “You have to go into nature to find a solution.”

Norbert has not only built an exemplary eco-lodge with a closed loop carbon cycle, but has also reforested large areas of forest. Alongside this, he breeds fish such as the koi and paku and keeps geese, turkeys, ducks and Brahma chickens in spacious coops.

White-necked jacobin (Florisuga mellivora) in flight.

Cloud forest

We are at 1,150 metres. I marvel at forehead bird nests swaying back and forth in the wind in the thin branches. The cloud forest lives up to its name. It’s like looking through a soft filter all the time.

Norbert has secured a 22-hectare plot of land, most of which is cloud forest. On the smaller part at the edge of the forest, he grows a variety of crops: Cabbage, papayas, shiitake mushrooms, dill, parsley, tree tomatoes, ginger, turmeric, mustard, rocket and Mexican glandular goosefoot, also known as meat spice epazote.

A cloud forest is very fragile.

The breathtaking cloud forest is home to 250 to 300 tree species. We step inside. It drips incessantly from above. Norbert enlightens me: “This is also called horizontal precipitation. Plants are masters at draining water. Here in the cloud forest, up to 30% of the moisture consists of dripping. A cloud forest is very fragile. Unlike other forests, this one would take something like 700 years to reforest.”

This mystical habitat is home to tapirs, pumas, ocelots, armadillos, anteaters, coatis, raccoons, rodents, coyotes and the jaguarundi, also called the weasel cat. Norbert has proven the existence of many of these species thanks to his infrared camera traps.

Cloud forest near Casa Maria.

More than 200 years ago, there was another German in Venezuela who pointed out that forests increase the ability to store water and contribute to cooling the climate: Alexander von Humboldt.

Norbert Flauger, with tireless commitment, hard work and rascal charm, has created something that lives up to the spirit of Humboldt. I hope it will be preserved for a long time. Norbert looks up, spreads his arms: “This is my treasure.” It’s more than that: it’s his life’s work.

Order TERRA MAGAZINE here (only in German):

Print and digital edition

Read now:

Pure inspiration

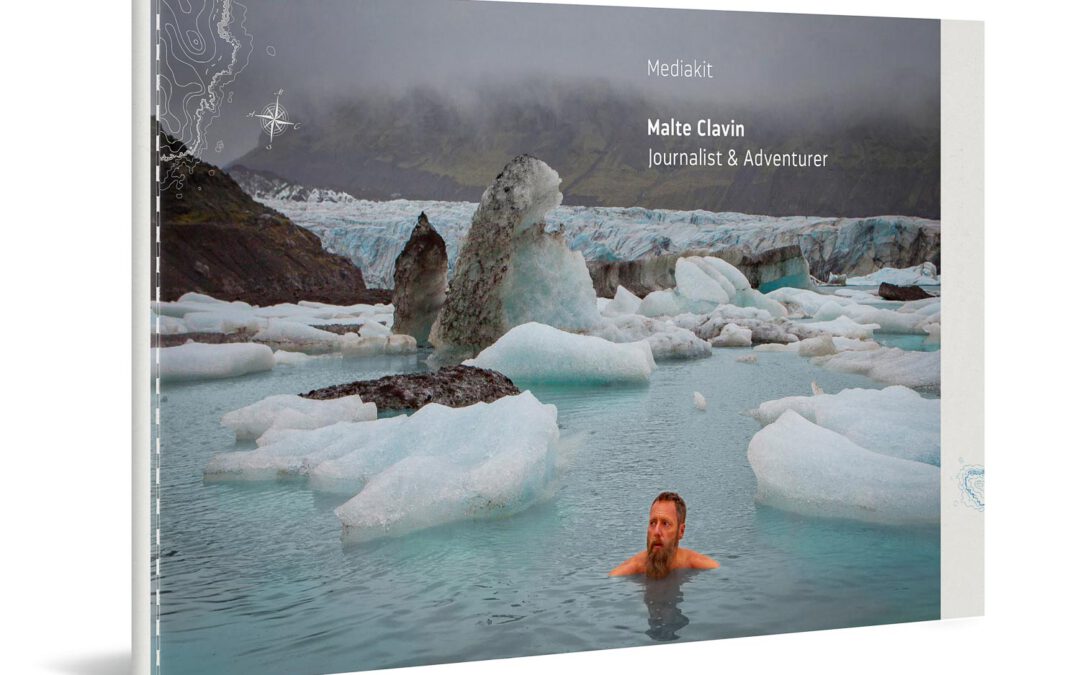

My new media kit 2025

< 1 Min.In this brand new 28-page media kit, I show you my work as an adventure journalist and speaker: Expeditions, travels, challenges – everything that excites me. Let yourself be inspired.

From South Africa's wilderness

Two lessons for life

8 Min.Suddenly I realized: I am in the habitat of lions, elephants, and buffalos. For three days. On foot. That was one of the most mesmerizing experiences I’ve had ever been on. Here are my two most important learnings.

Ranger training on the edge of the Kruger National Park

South Africa photo gallery

< 1 Min.Exploring the wilderness on foot in the midst of lions, elephants and buffalo? You can learn to do that. In summer 2019, I will join a field guide course in South Africa.