Published in:

Germany’s biggest nature travel magazine

12 pages| text & photography

Where Hollywood found Mars

“I have driven Matt Damon twenty-six times.” As Raed Suleiman pilots the jeep over a perfectly straight sandy track towards what must be one of the most magnificent rocky landscapes on earth, he pats the passenger seat with a laugh. “Right where you’re sitting now.” Paul, my travel companion, has the honour. I am in the back seat with two other passengers.

Raed is one of those people who can quickly fascinate you. I wonder how many times he must have shared his knowledge and the tales by now, it doesn‘t show. Everything wells up in a wonderfully fresh and lively way. A few years ago, Raed worked as a ‘fixer’, a kind of all-round facilitator for the Hollywood film ‘The Martian’, starring Matt Damon.

Welcome to Wadi Rum.

A weathered metal sign at the edge of the track welcomes us. Behind a hill, beyond a sandy plain, a jumble of reddish-brown rocks sprawls out. Biblical, epic, humbling.

We lumber on along the desert track. A few small dots appear below a rock face. Minutes later the dots join our caravan: desert guide Samer Abudagga, the Bedouins Abu Yousef, Ataallah and Nayef, five adult camels and the four-week-old baby camel Coco. We have four days of trekking in the desert ahead of us. We intend to pitch tents between rocky islands and gain insights into the life of the Bedouins.

The first leg is quite a challenge: we stroll through the sand for six hours. If you get tired, you can have a bone-rattling ride on the back of a camel. Our caravan uses the old historic trade route that connected Jerusalem with Mecca for over a thousand years.

Large quantities of iron have oxidised here and colours the sand a special red.

I ask Raed to teach me a few words in Arabic. “Wasalna” is an expression for joy. You will most definitely be able to use it in the next few days,” he says and pats me on the back. I raise an eyebrow. Raed continues: “Wadi Rum, that means the valley of shifting sands.”That is certainly true. The wind blows incessantly and whips up the grains of sand.

Wadi Rum seems like an endless beach where you will always be searching for water in vain. Towering blocks of sandstone and eroded granite rocks seem to have been left lying around in a haphazardly fashion. Their furrows, layers, bulges and ledges provoke my imagination. My mind conjures up mythical creatures, melting chocolate ice cream and futuristic apartment complexes.

72% of Jordan’s landmass is desert. Of this, Wadi Rum takes up an area of about 100 km long and 60 km wide. Large quantities of iron have oxidised here and colours the sand a special red. This is what Mars must look like. Or other desert planets.

Many Hollywood producers thought so too, and chased their actors through gorges, sandstone and dust here. They shot ‘Prometheus’ (2012), ‘The Martian’ (2015), ‘Star Wars Rogue One’ (2016) and the seven-time Oscar winning ‘Lawrence of Arabia’ (1962).

Alexis marvels at the grandiose rock formations and the unbelievably wide landscape of Wadi Rum.

However, it is not only movies about Mars that are shot here. From 1916 to 1918, Wadi Rum was partly the scene of the Arab Revolt. The Arabs fought for independence from the Ottoman Empire during the First World War. Their struggle was fuelled by the promises of the British secret agent Thomas Edward Lawrence, who was sent as a liaison to the insurgents.

However, the hoped-for independence never materialised. Despite the promise to hand over rule over all of Arabia to the Sharif, the victorious powers France and England, carved up the Arab world between them in the secret Sykes-Picot Agreement. The Arab leaders rightly felt betrayed. Many of the problems in the Middle East today are rooted in the broken promise made by T. E. Lawrence, who became famous as ‘Lawrence of Arabia’.

Many cultures have inhabited Wadi Rum since prehistoric times. More than 4000 rock carvings bear witness to everyday life of the people who lived here about eleven thousand years ago. In 2011, the rocky desert was added to the UNESCO World Heritage List.

The cliffs are mostly of sandstone and granite. Wadi Rum is about 800 metres above sea level, its highest elevation is Jabal Umm ad Dami at 1854 metres.

Devilish hot

Wadi Rum could also very well have been where Jesus wandered for 40 days and nights without food and water. Apart from hunger and thirst, he must have been tormented by the sweltering heat. The temperature can reach 50 degrees centigrade here. It is hardly surprising that all this bestowed the vision of encountering the devil upon Jesus.

Today it doesn’t really want to get hot. Clouds chase away the sky‘s blue, the wind picks up. After passing through a narrow gorge with vertical rock faces, we take our lunch break in the shade of an overhanging cliff. We gather the few twigs we can find to light a fire. Tea is made. Wonderfully sweet, with thyme and not too hot, it is soothing. Raed and Abu Yousef conjure up the traditional dish maftool from chicken, vegetables and bulgur.

With renewed energy we continue our hike through the Wadi al Hesmeh, the ‘plateau without water’. Fortunately, the sand is not too soft. I do sink in, but not so deep that I quickly tire. After a three hours hike, we reach our campsite for the night: Siq of Burra. Since time immemorial this has been a popular camping spot for Arab desert caravans. Once the rock here released precious water. For thousands of years it was dammed up. Today there is no more water here, only a name and a reminder: ‘Sad al roumeia’, Romeia Dam.

“Haboob,” he says. I see nothing which could herald the arrival of a sandstorm.

Before the sun sets, with combined forces we pitch up the unwieldy communal tent. The tarpaulin made of goat hair resembles a long, thick carpet. First we drive the pegs deep into the sand, then we heave the tarpaulin up the wooden tent poles so that it encloses our campsite like a windproof wall. Finally, we stitch the wall to the fabric of the roof.

While ceaselessly telling stories, singing, gesticulating, Raed prepares dinner. Abu Yousef helps out. It is getting dark. I join the two. Arabic class. Raed points to the slowly dying fire: hariq.

Ten minutes later, my fellow travellers and I break the traditional Jordanian bread called shrak and use it to spoon up the national dish mansaf, lamb in yoghurt sauce. Delicious.

Abu Yousef looks up at the sky and points towards the horizon. “Haboob,” he says. I see nothing which could herald the arrival of a sandstorm. Bedouins can read the sky and the sand. Perhaps he is right. In silence we sit beside each other and look up into the night sky. It is peaceful. When you are with the Bedouin, you experience the real original Jordan. With this thought in mind, I pull up the blanket over my head.

At night the tent opening that was meant to be lee side turns out to be the wrongly positioned. The wind has shifted and now blows directly onto those sleeping. I am out in the open, wrapped in a bisht, a traditional ankle-length open coat made of camel leather and goatskin. I wedge myself between the rocks as best I can. Not windless either, but snore-free.

If this patina-overlaid kettle could tell stories…

A Bedouin who takes hearts by storm

5 o’clock. The rhythmic grinding of coffee beans in the mortar wakes me up, the smell of freshly brewed coffee soon draws me to the Bedouin tent. The first rays of sunlight lend a majestic touch to the rocky walls surrounding us.

Wearing my bisht and protected from the morning chill, I watch Raed perform his breakfast ritual with the ‘Bedouin frying pan’: he mixes embers, ashes and sand into a fuming surface on which he pours the freshly mixed kebab dough. On our knees and sitting in a circle, we dip Raed’s warm to the touch bread art into bowls with halva, thyme, goat cheese, olive oil, date syrup and tahini. Such a delight. Voracious silence.

“Oha! Snow is falling in Petra,” Raed announces, looking at his mobile phone. Although the world-famous rock palace is only about 50 kilometres away, it can be up to 20 degrees colder there. The weather is deteriorating here as well. “We have a storm warning,” Samer sighs, cancelling the tricky hike for today.

“Haboob,” I suggest, raising my hand like a model student. “Ha-ha. No problem,” Raed replies, “Abu Yousef invites us to his desert camp.” I look at Abu Yousef, cheerfully say “Wasalna!” and he returns me his unique movie star smile.

After four hours of walking, a first glimpse of Abu Yousef’s camp urges us on. It is situated at the foot of a gigantic rock wall. The midday heat stings. We are still two kilometres away. Or three? Gauging distances in these vast expanses, without any points of reference, is difficult.

The ethos of self-determination, dominion and freedom over life is important to the Bedouins.

Abu Yousef shows no sign of hike-exertion. Light and elegant, he glides swiftly over the plain. Without headdress, but wearing a dark tailored jalabiya, the traditional clothing of Jordanian men. And wearing smart black leather boots.

Exhausted from the heat, sand and dust, I squat on a colourfully patterned carpet in the desert camp of Abu Yousef. Literally, his name means “father of Yousef”. Male Bedouins, as soon as they become the father of a son, take on his name. And Abu Yousef’s eldest son is called Yousef. Two wives bore him twelve more children, aged between five and twenty-four now.

Abu Yousef’s family belongs to the ‘Al Zawayde’ tribe, one of the two large families that divide Wadi Rum between them. The spirit of self-determination, sovereignty and freedom in life is essential for the Bedouin. They call the shots in Wadi Rum, often drive their cars without number plates, and the government lets them.

In the break the Bedouins Ataallah and Nayef quench their thirst with thyme-soaked tea.

Abu Yousef shows me a leather-bound book. In it, his family‘s history is recorded, seven generations in all. I can’t quite believe it just yet. This, the desert, this is his home. Knowing Berlin-Kreuzberg as I do, Abu Yousef is at home in this wild rocky steppe.

He knows seventy peaks by name, most of which he climbed as a boy. Barefooted. I look around and start to count: together there are 71 goats, 25 sheep, 3 camels and dozen chickens. Can he sustain his family on that? I wouldn’t know. I do know that Abu Yousef holds Bedouin traditions and values in high esteem and that he is committed to preserving them. He seems prudent. Calm and noble. This man impresses us all.

Abu Yousef kneels and lights a fire from the branches his sons have collected for him and puts on a blackened kettle. The scent of coffee and cardamom fills the desert air.

Cold coffee? Such a sin

Coffee is never just a quick cup in Jordan, but a sacred ritual. At least among the Bedouin. Wars were fought over a cup of coffee, marriages arranged, tribal relationships forged and strengthened. Abu Yousef pours himself a cup to test whether the coffee is hot enough. You shouldn’t be able to drink it all at once, that would mean Abu Yousef didn’t make enough of an effort. Serve cold coffee? Such a sin.

“The cup is held with the right hand,” says Abu Yousef. “We use the left one for other things, going to the toilet, for example. It is considered unclean. That is also important when it comes to eating.”

Blowing on your coffee to cool it down is not done. Instead, swirl the liquid around in the cup until you can drink it. Then you take three sips. No more, no less. More coffee? Then swing your cup back and forth. Want another cup? Lift the cup, but no more than three times, that would be disrespectful.

Now after coffee-time, Samer decides that we should hike back to the resting place from last night. A blustery wind now blows and we would be reasonably sheltered there.

“But don’t you think about jumping around in the middle.”

A rocky end

Hold on. Pulling up. Balancing. Stooping to cross under an overhanging cliff. The sandstone has a lot of traction, but still negotiating the footpath up to Burdah rock bridge is quite demanding for us summiteers. At difficult key passages, Samer, our super fit triathlete, lends us a helping hand.

It needs resolve, but I put my non-existing absence of vertigo to the test. “The bridge is stable,” Samer says, and with a sideways movement of his head towards the stone arch he signals me to go ahead. “But don’t you think about jumping around in the middle.” I am obedient. At the other end of the bridge, I feel somewhat proud.

In the afternoon Abu Yousef invites us for tea at his brick house in Wadi Rum Village. As soon as we arrive his youngest daughter Yaqueen runs up to my fellow travellers Michelle and Jessica, hugs them, pulls their arms in all directions to show them toys, her younger cousins and a tiled edifice with toilet and shower – a luxury in this area and proof that Abu Yousef takes good care of his family.

Burdah rock arch: I put my non-existent freedom from vertigo to the test.

Nachmittags lädt uns Abu Yousef zum Tee in sein Backsteinhaus in Wadi Rum Village ein. Dort angekommen, rennt seine jüngste Tochter Yaqueen zu meinen Mitreisenden Michelle und Jessica, umarmt sie, zieht ihre Arme in alle Richtungen, um ihnen Spielzeug zu zeigen, ihre jüngeren Cousins und einen gekachelten Bau mit Toilette und Dusche – ein Luxus in dieser Gegend und ein Beweis dafür, dass Abu Yousef gut für seine Familie sorgt.

Climb high, far sighted

Our last day. Today is a leisurely one, with only 440 metres elevation gain to cover. We ascend to the summit of the highest mountain in Jordan – Jabal Umm ad Dami – at an altitude of 1854 metres.

The trail starts at the foot of the mountain and after two and a half hours we reach the summit. The view across to Saudi Arabia is magnificent. I have this yearning. How I would love to continue on in a southern direction, crossing Saudi Arabia into Yemen, where the first Bedouins set off north in search of water in Abraham‘s time.

This panorama: rugged, wild, desolate nature where ever you look. No trace of civilisation. Unchanged for thousands of years. People come and go, their stories survive. It seems the desert belongs to no one but itself. Wasalna!

Read now:

Pure inspiration

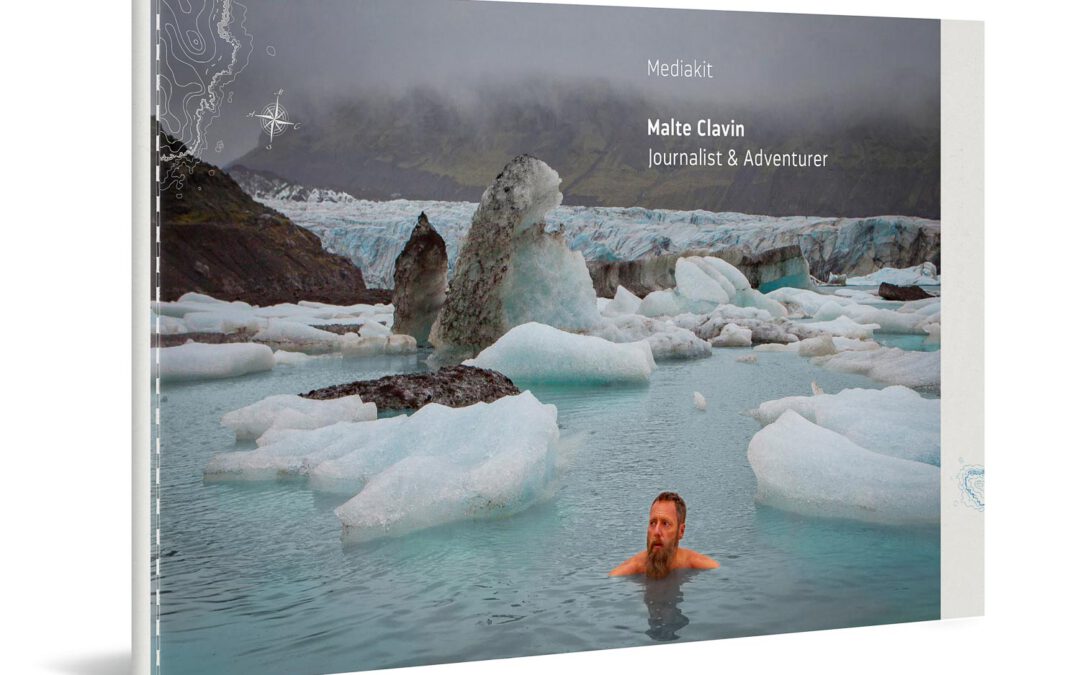

My new media kit 2025

< 1 Min.In this brand new 28-page media kit, I show you my work as an adventure journalist and speaker: Expeditions, travels, challenges – everything that excites me. Let yourself be inspired.

On the road with nomads

Jordan photo gallery

< 1 Min.The first day’s leg is already a tough one: we traipse through the sand for six hours. Our caravan is moving along the historic trade route that connected Jerusalem to Mecca for over a thousand years.

Son Doong in Vietnam

Expedition to the largest cave in the world

13 Min.To the center of the earth! The most spectacular trip I’ve ever done: the Son Doong cave expedition in Vietnam. First, it’s through leech-infested jungle. Then, abseiling down into the cave, over sharp rocks, through underground lakes, gigantic shafts. Absolutely breathtaking!