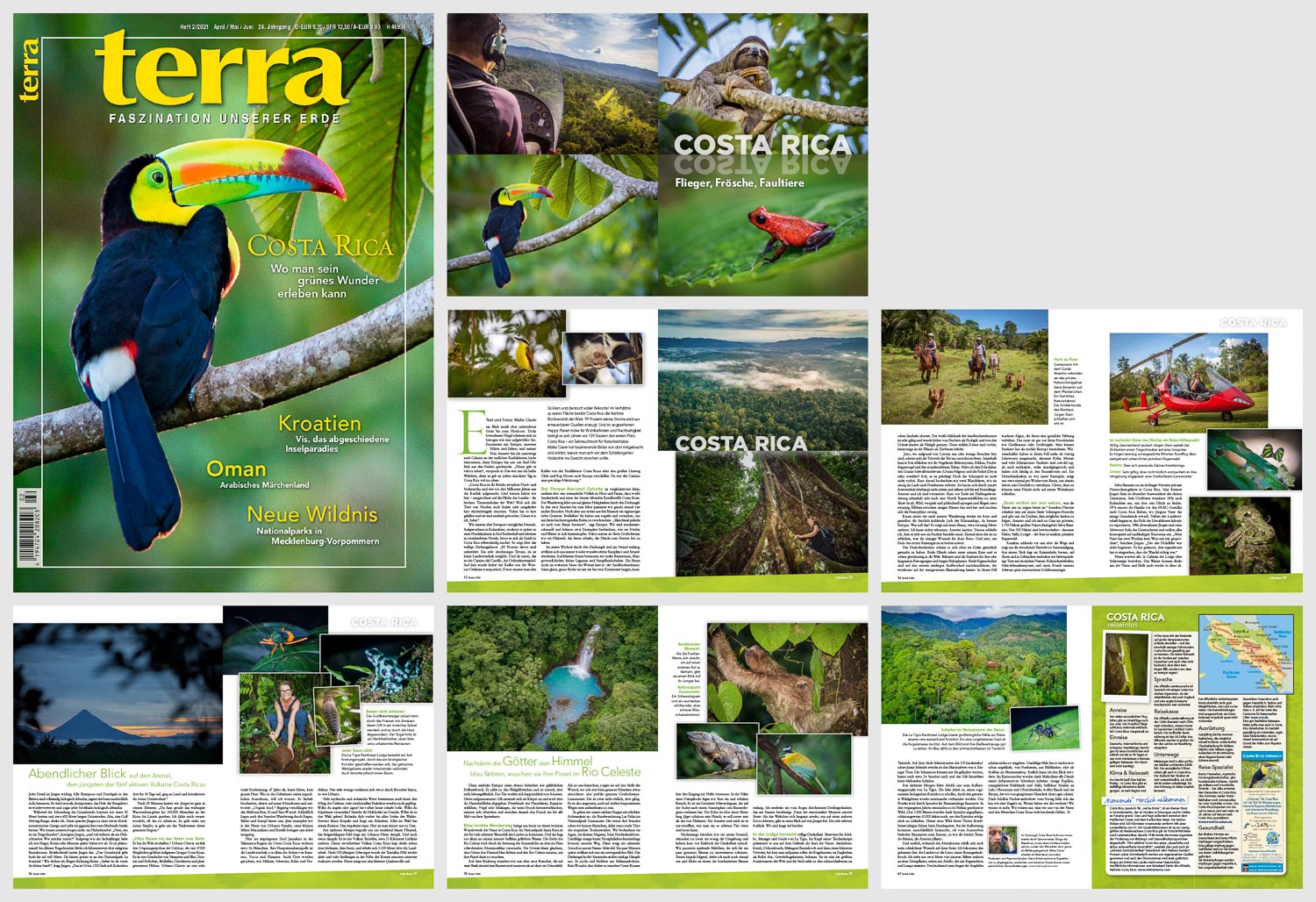

Published in:

Germany’s biggest nature travel magazine

Coverstory | 12 pages | text & photography

Fliers, frogs, sloths

My gaze sweeps across untouched green all the way to the horizon. Densely overgrown hills seem to move like a churning sea. Together with Enrique, our guide and driver, and my wife Annette, I am on my way to Cahuita on the Caribbean coast, slightly dazed, because Enrique has shooed us out of our beds at five in the morning. “There’s a lot to see today.” he promised. That wasn’t true. Because there is a lot to see in Costa Rica every single day.

“Costa Rica is the bridge between North and South America and only emerged from the Caribbean three million years ago. And why do we have the highest density of animal species in the world here – if you take into account the size of the country?

All animals migrating from north to south, or vice versa, had to squeeze through here. Many liked it here, also because of the wind and the humidity, and decided to settle down. Just like me, ha ha!”

We marvel at Enrique’s excellent German. Raised in Colombia, he later studied at a hotel academy in Bad Reichenhall in Germany, worked in various hotels before setting up his own business as a guide in Costa Rica.

He points across the green undulating jungle sea. “Eighty percent of it is untouched. It’s a very steep terrain, no agriculture is possible there. And down there, that’s the Camino del Carrillo, the ox-cart trail. It was used to transport coffee from the west to the east coast. Before that, the coffee had to be shipped from the Pacific coast of Costa Rica to Europe via a big detour by way of Chile and Cape Horn. So the Camino was a big shortcut.”

We take a break in a street restaurant with a display that stretches over twenty metres. Plates are quickly scooped full of gallo pinto, ‘spotted rooster’. The traditional dish consists of white rice and black beans. Both are fried in a pan, stirred through, seasoned and served with side dishes such as corn tortillas, egg and white cheese (queso frito).

High above us, a strange, deep grunt sounds from the trees. Howler monkeys.

We pass Cahuita on the southern Caribbean side. It is considered the home of Afro-Caribbean culture with sounds of reggae and calypso music now playing on the car radio. After a while, I think I recognise the differences between salsa, cumbia, son, mambo and merengue, but fail miserably in identifying each new song – to Enrique’s amusement.

You have to be born here to recognise the differences and, above all, to be able to dance passionately to them. Despite all the spirit of discovery, this will probably remain an inaccessible world for me.

The Parque Nacional Cahuita is comparatively small, but includes an amazing variety of flora and fauna, plus white sandy beaches and one of the last living coral reefs in Costa Rica. The hiking trail leads us on smooth wooden planks through the jungle. In the two hours to the sea, we pass just four other visitors.

High above us, a strange, deep grunt sounds from the trees. Howler monkeys! They have spotted us and are trying to scare us away with their fearsome calls. “Sometimes they pee down from the tree,” adds Enrique.

We are quiet as mice and can watch two specimens stuffing fruit and leaves into themselves. They use their prehensile tail like a tether that allows them to dangle around and keep their hands free to feed.

Alternating between jungle and beach, beautiful resting places and beach sections open up to us again and again. In a small space, we marvel at the diversity of ancient giant trees, mangrove thickets, small lagoons and marshlands.

One tree literally stands out: the sand bush tree. Its smooth, grey bark is covered with 1 to 2 cm long, conical spines. The white milky sap of the sand bush tree is very poisonous and was used by fishermen as a fish poison and by the indigenous people as an arrow poison. Those wild times are over, nowadays the trunk is popular as an ornamental tree.

Together with Anselmo we explore Selva Bananito on horseback. A wonderful nature experience! Jürgen’s shepherd dogs join us.

Now that there are very few visitors here due to Corona, the wildlife seems to be reclaiming the terrain. Within a short time we spot the species of birch tyrant, pelican, magnificent frigate bird, and the beautiful toucan. Did I mention the zebra butterfly, the green moth (Urania fulgens) and the flame (Dryas iulia)? Ah, it is magnificent. But the spectacle is not over yet.

Shortly afterwards we observe two raccoons busily rummaging through the foliage for something to eat. They are not disturbed by our presence at all and come within arm’s length. Annette and I are enchanted. Shortly before the end of the half-day hike, a horde of capuchin monkeys put on a show. Wild, nervous, quick as an arrow and playful, about twenty monkeys kick, jump and fly back and forth between a handful of trees and compete for the feeding places.

Then everything gets even louder, faster and more aggressive when they spot a green iguana resting on a five-metre-high branch, giving the impression that nothing could disturb its peace. Now that the capuchin monkeys have no attention left for me, I can approach them, telephoto lens at the ready.

I need all my arm strength to hold the lens and follow them at literally monkey-like speed. After about twenty minutes, my arm is at the end of its tether and I am at the end of my patience. I return exhausted, my T-shirt soaked, but also with a handful of decent pictures on the memory card.

We are rewarded with a beer and then climb back into the car. Five minutes later, I’m nodding off in the wonderfully cool air of the air con when Enrique hits the brakes. What’s that about? He points to a tree about twenty metres away. I can’t see anything. Annette whoops with glee. From this I realise that it must be a sloth. To catch a glimpse of one, was her only wish for this trip. And now, at the end of the first day of the journey, the time has already come.

The three-toed sloth seems to have made itself comfortable up in the branches. Both hands rest under its chin and it gazes equanimously into the world.

Sloths are known for their very slow movements and long resting phases. Both characteristics are due to the extremely low metabolism, which in turn is based on the low-nutrition leaf diet. Algae grow in their fur, which gives them a greenish colour. This also camouflages them from their predators such as big cats or birds of prey.

You could almost call sloths mobile biotopes: Scientists have identified more than forty creatures in their fur, including beetles, moths and many parasites. Sloths are both diurnal and nocturnal, strictly solitary and often reside in treetops. A three-toed sloth, like our specimen, only comes down from the tree about once a week to do its business away from it. Clever, because this way its enemies can’t figure out where it lives.

Selva Bananito

“Let’s see what nature is willing to show us.” Anselmo Harriett shoulders his telescope mounted on a tripod and signals us to follow him as silently as possible. Annette and I are guests in the private, 1,750-hectare Selva Bananito nature reserve. Only 350 hectares are cultivated, including fields, stables and lodges – the rest is untouched, primary rainforest.

Anselmo creeps ahead of us over paths, meadows, forests and shows us the awakening animal world in the early morning before sunrise. A baby caiman peeps out of a pond, on branches and in bushes we discover colourful animals with equally exotic names: boat-billed heron, sulphur-masked flycatcher and a frog called black-green marbled golden treecreeper.

Selva Bananito is an important pioneer of private nature reserves in Costa Rica. Its owner Jürgen Stein is a third-generation German emigrant. His grandfather emigrated to Colombia in 1926 to find his fortune there. In 1974, the family had to flee from the FARC guerrillas to Costa Rica, where Jürgen’s father acquired the current property. In addition to farming, he began the lucrative export of wood from the jungle giants.

In 1986, Jürgen and his sister Sofia took over the business and consistently converted everything to sustainable tourism. “My father didn’t speak a word to me for a fortnight.” Jürgen reports. “The old woodcutter was not amused. It took time, but eventually he realised that the change was right.”

„It’s not about my family, it’s about the drinking water of this entire region“

Today, all 16 of the lodge’s cabins are powered by solar energy. The water comes directly from nature and also drains back into it. Every detail is important to Jürgen: all shampoos and shower gels in the bathrooms are completely biodegradable, and you are expressly not allowed to use your own. That is persuasive.

While exploring the property, we enter a 20-metre wide and about 400-metre long green strip. OK, that must be a golf driving range, I think. Then Jürgen walks to a somewhat oversized garage and pulls out a gigantic red mechanical insect. We can’t believe our eyes: it’s a helicopter. “No, it’s a gyrocopter.” corrects Jürgen, “And much safer than a helicopter. Who wants to go first?”.

Excited like a six-year-old, I raise my finger. Less than ten minutes later we take off. It is phenomenal. In the open gyroplane I look out over kilometres of sap-green treetops. Jürgen calls this a broccoli forest. Tears of emotion well up in my eyes. “The property rises up to 640 metres.

Back there it borders on the national park ‘La Amistad’, which was declared a world heritage site by UNESCO in 1983.” We turn off, flying towards the lake. “Do you see that little island up ahead?” Jürgen asks, “That’s Uvita. Columbus stayed there for 18 days in 1502, went ashore and contacted the first indigenous people.”

After 20 minutes we land. Jürgen is completely in his element: “You’ve seen the most important water protection area for 150,000 people on the coast as far as Limón. I feel responsible for protecting all that. It’s not about my family, it’s about the drinking water of this entire region.”

Not everyone is as animated by the spirit of nature and animal protection like Jürgen Stein. Many Ticos, as Costa Ricans call themselves, see hunting as a birthright. “Every one of my employees has a poacher in the family,” Jürgen sighs, “you can’t talk to them about values, conservation and such. The only thing that helps is fences, camera surveillance, education in schools and, especially, stricter laws.”

And then above all, keep going. Jürgen Stein will do so. Until then, nature stands a good chance here.

A highlight of our trip: Completely unexpectedly, Jürgen Stein conjures up a gyrocopter on a grass runway far from civilisation. Twenty unforgettable minutes of sightseeing flight over largely untouched primary rainforest follow.

At the Cabécar in Jameikari

“Cibu Kama is the father of God. He created the world.” Urbano Chavez tells the origin myth of the Cabécar, Costa Rica’s largest indigenous group with 17,000 members. It is a story of vampires, excrement, blood, thunder, wind, earthquakes, cocoa, umbilical cords, torsos, howler monkeys, deer, rabbits, snails, armadillos, iguanas and flattened fleas.

Urbano Chavez cuts a very energetic figure. 47 years old, no wrinkles, no grey hair. What is the secret of his youthful appearance, I want to know. He smiles modestly, points to our dinner and answers “organic food”. We eagerly devour the meal of rice, egg and taro root. After all, we have done three hours of hiking through rain, streams, swamps and steep climbs. Now we are munching away in the wooden hut of Urbano’s family, his little sons Maximiliano and Ketelik eyeing us curiously.

About 36 people live here in the remote village of Jamaikari in the Talamanca region of eastern Costa Rica. Their main source of income is agriculture, especially the cultivation of bananas, yuca and plane trees. Animals are also being raised, such as chickens, pigs, cows and turkeys. Very few earn extra money from visitors, like Urbano.

The Cabécar villages are unique in that the houses are not grouped together around a central place, but are scattered, sometimes kilometres apart.

The pregnant woman must be frightened with the dead bird and eat its heart raw.

Many mythical and archaic customs still define the daily life of the Cabécar, many traditional practices are still maintained. Want to fish or hunt? Don’t eat hot sauce beforehand. Want to avoid nightmares? Put charcoal on your face. Want to go into the forest? Thank all the souls of the forest beforehand. Show them respect and ask for permission. In the forest, everything has its owner. That is respected. You are only ever a guest here.

The Cabécar also believe that the sex of a child can be determined long before birth. And if, for example, a girl is found in her mother’s womb, she can be endowed with the quality of diligence. To do this, one kills a forehead bird, whose females are considered to be very industrious, while the males are considered to be limited and lazy. The pregnant woman must be frightened with the dead bird and eat its heart raw. If, contrary to expectations, a boy is born, bad luck, because then it is said that nothing good will come of the poor fellow.

Probably the most touching moment of our trip: We discover a three-fingered sloth on a tree, soaked by the rain. As she stretches to climb another branch (and it takes time…), she gives a glimpse of her young. A very rare sight. We are deeply touched for a long time.

The next morning we are greeted by a bright blue sky, the cleared field around Urbano’s hut is steaming. And something else is steaming, it is the volcano Turrialba, about 25 kilometres away as the crow flies. This second highest volcano in Costa Rica is right next to the highest, Irazú, and rises 3325 metres above the landscape. After 150 years of silence, Turrialba only became active again in 2006 and many settlements near the crater had to be temporarily evacuated. Today, only a small cloud of smoke rises, similar to the emission of an industrial chimney.

Then Enrique discovers a pretty but dangerous strawberry frog. It belongs to the poison dart frogs and is toxic, but not life-threatening. The animal feeds mainly on ants. The ingested poison accumulates in the body and is released through the skin surface. Predators such as coatis, capuchins, birds or snakes that swallow a frog poison their digestive system, vomit and then learn to take the frog off the menu once and for all.

Ink box for the gods

An easy hike today brings us to another of Costa Rica’s abundant natural wonders. In the Santa Rosa National Park you can marvel at what many consider Costa Rica’s most beautiful waterfall. And that is mainly due to the colour of its intense light blue coloured water. The colour of the Rio Celeste is caused by the scattering of sunlight on the aluminosilicate suspended in the river. The indigenous people believed that gods coloured the sky blue and used the Rio Celeste to rinse their brushes in.

On the way back, we are surprised to see two visitors sitting on a bench staring at a tree root as if it were an idol. Enrique makes a funny remark and then the two point to the root, on which only a closer look reveals something: a perfectly camouflaged griffin-tailed lance viper. It is definitely poisonous, but not lethal. So it is recommended to always be alert, even on busy paths.

So we do start our next stage with increased attentiveness: The circular hike Las Pailas in the Guanacaste National Park. For the first three hours we see no people, but all the more so animals of the tropical dry forest. We watch an aguti nibbling fruit. They belong to the rodents and are about the size of beavers. Nuts, leaves, small branches and roots are also on the menu.

Hunters value its meat, it is said to be more tender than that of chickens.

Countless orange-coloured nymphalid butterflies cross our path and a strange scent enters our nostrils: sulphur. A few minutes later, an unforgettable image opens up: the jungle is boiling! Fumaroles emit stinking vapours. It hisses and bubbles from mud holes. No wonder that many a Tico once suspected that this was the entrance to hell.

We take a break near a steam hole in the dry forest. Then we get a visitor. It is a common black iguana that has left its tree refuge in search of a place to sunbathe. The lizard is over one metre long. Hunters value its meat, it is said to be more tender than that of chickens. For Annette and me it is difficult to imagine that such a beautiful animal can be killed and eaten.

We move into a new domicile, familiarise ourselves with the surroundings in pairs and return shortly before nightfall. We pass girls playing, who seem to be interested in a few heavily trimmed trees. Following an impulse, I turn around again and look along one of the trimmed trees. I spot a three-fingered sloth, soaked by the rain, climbing down a trunk. Then the most touching moment of our trip: As she stretches to climb onto another branch (and it takes time…), she allows a glance at her young. A very rare sight. We are deeply touched for a long time.

La Tigra Rainforest Lodge

The lodge is in complete darkness. Showtime for Adolfo, manager and guide of La Tigra. In the cone of his torch, he presents us with the stars of nature on the grounds: the hourglass frog, bullfrog, mahogany tree frog and then a smaller representative to watch out for: the bullet ant. It is one of the largest ant species in the world and its sting is one of the most painful in the animal kingdom. On the sting pain index of the US insect researcher Justin Schmidt, it reaches the maximum value of 4. The only consolation: the pain can be relieved with ice, subsides after about 24 hours and the poison leaves no permanent damage.

The next morning we trudge deep into the forest again, sheltered from the sun by more than seventy different species of trees, including fishtail palms, cedrels, walking palms and rain trees. We marvel at tireless leaf-cutting ants, the truth-tooth-sized rusty-bellied guan and industrious mariola bees. They produce a medicinal honey that is used by many Ticos for a variety of eye problems. It is also effective in healing infections, pain, respiratory problems and as an antiseptic for wounds.

Evening view of Arenal, the youngest of Costa Rica’s five active volcanoes.

Adolfo takes us to the reforestation project of La Tigra. The idea is to create a so-called biological corridor through which separated forest areas are reconnected through reforestation. The project is financed by donations for tree seedlings. Among the donors are several German companies, including Telekom. In the past few years, 46 hectares of protected forest have been created and more than 3,000 trees have been planted thanks to donations. This new forest offers animals essential protection when crossing it. Only native tree species, often threatened with extinction, are used in the reforestation, like the two tostado trees Annette is planting today.

The main motivation of many donors is CO2 compensation. This carries credibility and the project is making good progress, but there is still a lot to do. Adolfo speaks of an estimated 10,000 trees that are needed to successfully close the corridor.

And finally, during dinner, my hidden wish for this trip comes true. I get the secret star of the country in front of my lens: a red-eyed tree frog. I stand only two metres away from our plates at a green plant, next to me Adolfo, who assists with umbrella and lamp. Nothing seems to escape the amphibian’s bright red eyes. He has looked at me countless times before, from postcards, picture books or as a stuffed animal in the museum shop. Finally I can return the gaze.

Thanks to the macro lens, all the details of his colourful beauty become visible in the camera viewfinder: huge pupils, orange clinging hands and feet, light blue stripes on his body, upper arms and thighs, a white belly and a body that seems to be covered in grass-green glossy varnish.

After Adolfo’s night walking show the day before, this almost feels like an encore. What have we done to deserve this? We don’t know. We only know that we feel richly endowed by Costa Rica’s nature and people. Enriched by these countless impressions, with much respect, humbleness and gratitude, we return home.

Order TERRA MAGAZINE here (only in German):

Print and digital edition

Read now:

Pure inspiration

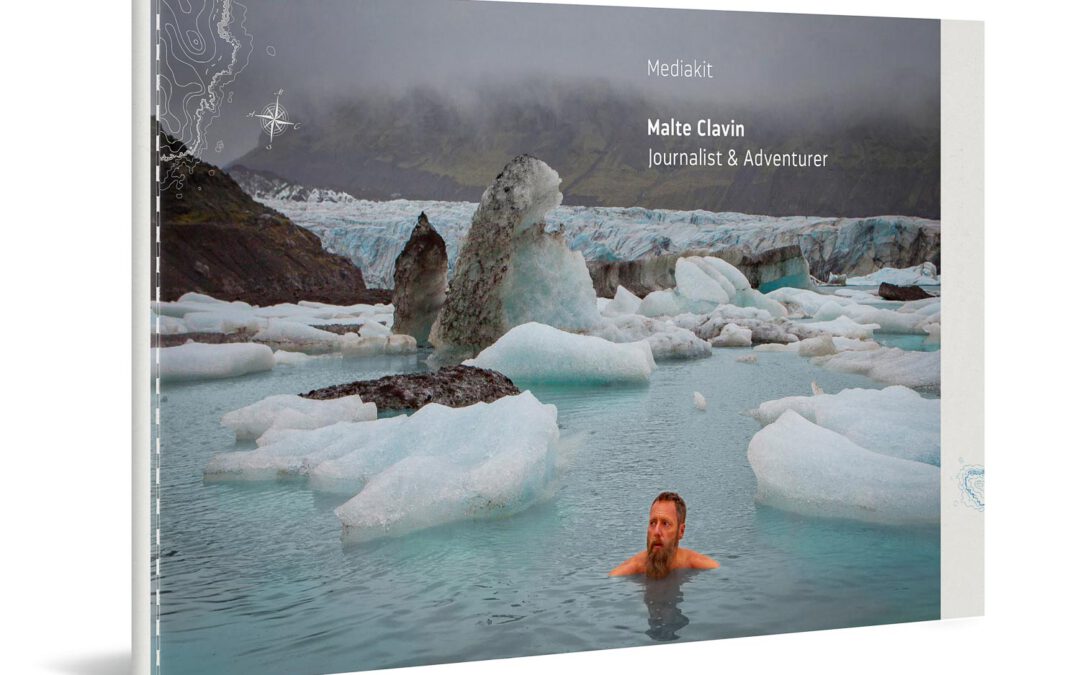

My new media kit 2025

< 1 Min.In this brand new 28-page media kit, I show you my work as an adventure journalist and speaker: Expeditions, travels, challenges – everything that excites me. Let yourself be inspired.

Colourful eco-paradise

Costa Rica photo gallery

< 1 Min.Shortly before the 2nd lockdown, I take the opportunity for a short escape to Costa Rica. In almost deserted national parks, an exuberant plant and animal world awaits me. A detailed article on my trip will appear in Terra magazine in April 2021.

Long-term travel with kids

Family time in Sri Lanka

30 Min.Ancient royal cities, endless sandy beaches, luxuriant flowers and exotic animals – the name Sri Lanka justifiably means “shining land”. The island in the Indian Ocean was our dream destination. I spent five months in Sri Lanka with my wife Annette and our daughters Amelie and Smilla.