Published in:

Germany’s biggest nature travel magazine

12 pages | text & photography

Bled – pearl of the Julian Alps

“Can you see the castle up there?” asks Annette, pointing to the 139-metre-high limestone cliff on which the mediaeval fortress perches like a stone sentinel over Lake Bled.

The boatman rows us silently across the water

A pletna already awaits at the boat jetty, one of those traditional wooden rowing boats that have been heading to Slovenia’s largest island for centuries. The boatman rows us silently across the water. Left and right we pass well-maintained lake villas from the Belle Époque era, their neoclassical façades gleaming through chestnuts and lime trees. After ten minutes we reach the 2,000-square-metre island, which was already settled in prehistoric times.

Like a romantic painting, Lake Bled spreads out between the wooded hills of the Julian Alps, with a fairytale island and baroque church in the middle – a scene that has enchanted visitors for centuries.

99 steps lead up to the baroque Church of the Virgin Mary, whose history reaches back to 1142. Annette rings the famous bell — cast in 1534 by Franciscus Patavinus in Padua, legend has it that it fulfils every wish.

After 30 minutes of sweaty climbing we reach the upper courtyard

The return journey brings us to the foot of Bled Castle, Slovenia’s oldest fortress. A steep forest path winds through beeches and chestnuts up to the plateau. After 30 minutes of sweaty climbing we reach the upper courtyard.

Through the lush green canopy of chestnuts and beeches, Villa Bled gleams in classical splendour – once the president’s summer residence, now a luxury hotel on the shores of the emerald glacial lake.

Then the castle’s true treasure reveals itself at the southern bastion wall: a breathtaking panoramic view over the lake, wooded hills and the peaks of the Julian Alps.

“Now there’s only one thing missing,” says Annette with a grin as we arrive back at the lakefront and she pulls me into one of the many lakeside cafés.

A sweet conclusion to a wonderful day by the lake

Then a plate lands on our table bearing a celebrity: the Bled cream cake. The golden-brown puff pastry creation with velvety vanilla cream and powdered sugar-dusted top melts on our tongues — a sweet conclusion to a wonderful day by the lake.

The Bled cream slice, a heavenly yet calorie-rich combination of delicate puff pastry, velvety light vanilla cream and a topping of airy beaten egg whites, is the culinary symbol of Lake Bled.

Through wild gorges and springs

“Rockfall!” warns Annette, pointing to the warning signs at the entrance to Vintgar Gorge. As we put on our protective helmets, the scent of wild garlic rises to our nostrils. Just minutes later we’re gliding over the first wooden walkways that snake between house-high limestone cliffs.

Then a geological masterpiece opens up

Bird song fills the humid air — in one spot I hear four different species. Then a geological masterpiece opens up: the emerald-green Radovna rages over polished terraces through the 1.6-kilometre-long gorge that has been carved out between the hills of Hom and Boršt by water masses.

Through the wildly romantic Vintgar Gorge, the emerald-green Radovna thunders over smooth limestone terraces.

More than 600 plant species thrive in this gorge

We also discover blooms of alp petasites that hover like delicate shuttlecocks in the gentle light. More than 600 plant species thrive in this gorge.

After an hour we reach the 13-metre-high Šum waterfall, where the Radovna thunders into the depths. After another hour through dark forest we’re back at the starting point.

The delicate seed heads of the Petasites paradoxus float like silver shuttlecocks in the soft light of the Martuljek Gorge.

“I know nothing more beautiful in Europe!”

The famous English scientist Sir Humphry Davy wrote about Zelenci in the 19th century: “I know nothing more beautiful in Europe!” [Original English quote researched and confirmed]

The Martuljek waterfalls finally reveal themselves as a hidden amphitheatre of the Julian Alps.

Between rose-coloured dolomite rocks, the emerald-green Martuljek dances through its wild riverbed.

Guide Alenka leads us to the wild cascades where meltwater plunges into the depths over high limestone terraces. “By the way, Slovenia is Europe’s biodiversity champion,” she reveals to us, “with about 24,000 plant and animal species and more than a quarter of them endemic.”

Alenka points to the trees around us

A golden eagle soars high above the ridges whilst a white wagtail hops by the water.

Alenka points to the trees around us: “Wooden shoes were carved from such beech or birch wood. Basketwork was woven from willow twigs. A baby cradle contained up to six different woods.”

Through this mighty limestone portal of Martuljek Gorge opens the view to the turquoise Radovna – a geological masterpiece carved by millennia of erosion.

She continues: “Beech lye cleaned dishes and floors. Lime wood formed spoons and spinning wheels, ash became skis and cart wheels. Every tree, every plant had its purpose. Our ancestors read nature like a textbook, knew almost all fungi, plants, woods. The forest was simultaneously hardware store, workshop and pharmacy — a closed cycle without waste.”

Annette and I listen spellbound to Alenka’s words

Annette and I listen spellbound to Alenka’s words. What wisdom, we both think. For centuries people lived without knowing what we call it today: sustainably.

Like a fairy-tale flower tower, a rampion (Phyteuma) rises from the moist undergrowth of Vintgar Gorge.

Cycle tour with wine tasting

The e-bikes hum quietly over the gentle hills of Brda whilst a panorama spreads before us that’s reminiscent of Tuscany.

On lightly trafficked roads we effortlessly climb the metres of elevation

We glide past abundantly blooming rose bushes and terraced vineyards that stretch like a green carpet to the horizon.

On lightly trafficked roads we effortlessly climb the metres of elevation we need to cover to reach the picturesque and excellently preserved villages.

Like a painting, the cultural landscape of Brda stretches between forested hills – here Slovenian winemaking tradition and Mediterranean lifestyle merge.

We reach Patrick Simčič’s winery. The hospitable vintner manages 11 hectares of vineyards in his home region of Biljana in the fourth generation. “For each grape variety we have a special place in the vineyard,” Patrick explains whilst pouring us his golden Moja.

The wine unfolds velvety on my tongue

In the glass I swirl the amber liquid against the endless sky. The wine unfolds velvety on my tongue — mineral, elegant, with a vibrant acidity that comes from the sandy marl soils.

The fine wines of the Brda winegrowers are gathered in an old oak barrel – from mineral Sauvignon Blancs to elegant Chardonnays, each bottle reflects the unique microclimate – and probably also the thirst – of this Slovenian wine region.

Patrick emphasises: “My philosophy is to produce flavourful, fruity wines full of harmony. They should encourage drinking another glass straight after the first.” That he succeeds in this is evidenced by the countless framed awards in the light-flooded showroom.

Time seems to stand still

Time seems to stand still as we sit on the terrace, have another glass and look out over a cultural landscape where Slovenian wine-making tradition and Mediterranean lifestyle merge. We can well understand why Brda, as a granary that bears fruit almost all year round, once delighted Austrian emperors too.

Lushly blooming rose bushes, little traffic on the streets, magnificent views – many villages in the Brda region are wonderful destinations for cyclists.

50 shades of culinary art

It’s pouring with rain when we reach Hiša Franko. Thanks to the umbrellas that Ioannis Chitzios, the maître d’, hands us whilst still in the car, we enter the restaurant dry.

Awarded with three Michelin stars

As the first Slovenian establishment, Ana Roš’s restaurant was awarded three Michelin stars in 2023 — a fairytale rise for the autodidact who took over her parents-in-law’s inn without culinary training.

From the “50 Shades Of Red” menu at the award-winning Hiša Franko restaurant in Kobarid: this dish is called “Spring Harvest”.

’50 Shades of Red’ — 16 courses await us, each dish served in a different, handmade vessel. Whilst Al Green’s Simply Beautiful plays softly from the speakers, the waiter in floral uniform hands us a bowl with rich green moss.

That’s exactly what it’s about: experiencing

“Experience the forest,” he smiles mildly. That’s exactly what it’s about: experiencing. The quail egg wrapped in leafy vegetables with Alpine caviar melts velvety on the tongue, followed by the artfully arranged Spring Harvest — a poem of regional wild herbs, vegetables and edible flowers.

After three hours of culinary magic at the legendary Hiša Franko, Annette and I feel incredibly grateful, humbled and blessed – thanks also to Ioannis Chitzios (centre), the “comis of front of the house” at the three-star restaurant.

All ingredients are regional and seasonal, many from their own garden behind the house. Only the Austrian Alpine caviar breaks the rule.

We feel incredibly grateful, humble and blessed

At one of the seven wooden tables in total, Annette and I become increasingly beside ourselves with these never-before-experienced flavour magic. After three hours we feel incredibly grateful, humble and blessed.

One of a total of nine local wines served to me during the 16-course meal.

On the trail of forest bears

The twenty-minute drive to the hut becomes an odyssey: temperature drop of eleven to eight degrees announces itself. Hail and thunderstorm. Left and right of the road water collects, when driving through it splashes two metres high. And in the spartan wooden hut in the forest of Markovec things were to continue excitingly.

A young brown bear with watchful eyes looks just past our hide

Arrived there, after a short wait a young brown bear with watchful eyes looks just past our hide. In the rain he wanders through his territory, we observe his every movement from a safe distance.

A young brown bear keeps a watchful eye on us, narrowly missing our hiding place. Slovenia is home to one of Europe’s most stable bear populations, with around 1,000 animals living in the dense forests of the Julian Alps and the Dinaric Mountains.

Game wardens lure the omnivores with scantily measured maize to observation points. Then the mother of the young animal appears: a female bear weighing about 300 kilograms. Now she shows her massive teeth.

Annette and I hold our breath

Annette and I hold our breath as the mighty creature searches for food not far from our hide.

With over 900 brown bears, Slovenia is one of the countries with the highest bear density worldwide. Controlled observation from secure hides enables unique insights into the behaviour of these awe-inspiring forest dwellers.

A young brown bear wanders through its territory near Markovec in the rain. Controlled bear watching from safe hiding places provides unique insights into the behaviour of these impressive forest dwellers.

Journey to the cave bears of the Ice Age

Guide Gašper Modic hands me overalls, wellington boots and head torch. Then we enter this unique water cave alone, which is considered the best protected cave in Slovenia, almost completely natural and without artificial lighting. The 8,273-metre-long water cave houses 22 underground lakes and is considered one of Europe’s most beautiful stalactite caves.

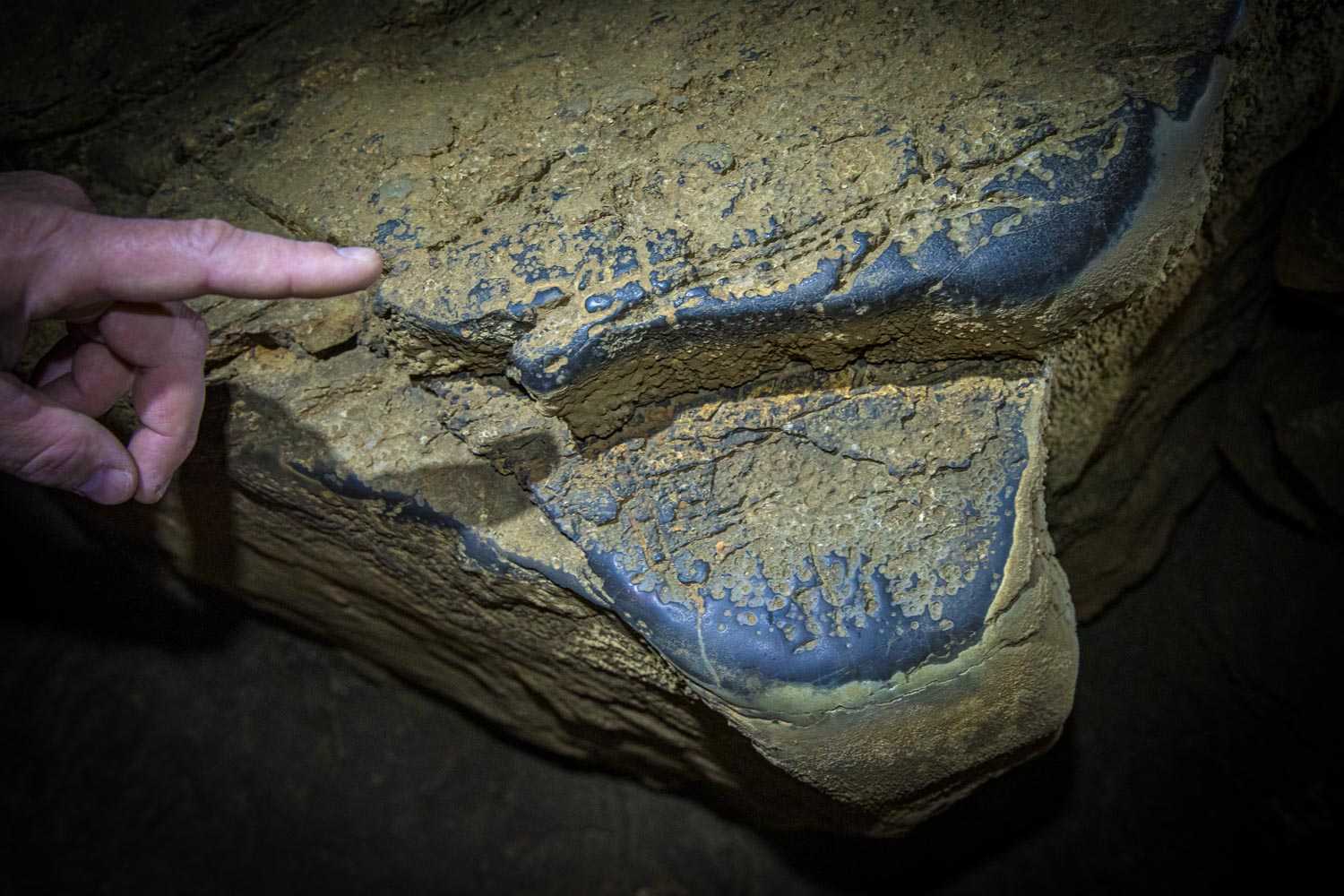

Here up to 200 cave bears squeezed through annually

On some of the natural light-brown rock boulders in the first chamber I recognise black polished surfaces — here up to 200 cave bears squeezed through annually for over 25,000 years and literally polished the passages with their fur.

In Križna Cave, these smooth black surfaces on the limestone bear witness to thousands of years of use – countless cave bears rubbed their fur against them, leaving smooth marks that could only be preserved in the protected cave climate.

In the Ice Age the temperature in the hibernation quarters — called bear tunnel — of the massive cave bears weighing up to 1.5 tonnes was about 8 degrees, whilst outside temperatures of up to minus forty degrees prevailed.

With a constant water temperature of eight degrees Celsius

Now Gašper navigates his yellow inflatable boat through the waters with a constant water temperature of eight degrees Celsius, past millennia-old stalactites and stalagmites. The silence is broken only by the gentle splash of his paddle.

Gašper Modic glides through one of the emerald green lakes of Križna Cave in a yellow rubber dinghy. The 8,273-metre-long water cave is home to 22 underground lakes and is considered one of the most beautiful stalactite caves in Europe.

“At the moment we have extremely clear water. Everywhere we can see right to the bottom,” he explains proudly.

This cave is an unreal beauty

During the photo stops, which we illuminate elaborately with many lamps, Gašper appears to me between the monumental stalactite columns and ancient limestone formations like a guardian of the underworld. This cave is an unreal beauty, and everyone who visits it can still feel today what early explorers might have felt.

Gašper Modic stands between the monumental stalagmites of Križna Cave like a guardian of the underworld. The emerald green water at his feet reflects the ancient limestone formations, creating a scene of unreal beauty.

Canyon of eternity

In the monumental Mahorčič Cave, part of the Škocjan cave system, guide Borut Lozej shrinks to a miniature before titanic limestone walls. Daylight penetrates through the natural portals and transforms the rock massif into a cathedral of light and shadow.

Since 1986 the Škocjan system has been on the UNESCO World Natural Heritage list

The caves, passages, shafts, natural bridges and swallow holes of Škocjan were created by the River Reka, which disappears here in the karst underground and only resurfaces 39 kilometres further on in Trieste. Since 1986 the Škocjan system has been on the UNESCO World Natural Heritage list.

The Reka River rushes over polished limestone banks through the depths of the Škocjan Cave. Guide Borut Lozej examines a basin that has been shaped by thousands of years of water power and erosion.

Borut, who has been exploring caves for over 30 years, reports on the first adventurous discoveries of the cave.

“The first cave explorers climbed barefoot around in caves“

“The first cave explorers climbed barefoot around in caves, had candles on makeshift helmets. Because of the roaring river and the irritating echoes, people communicated back then with signal horns and specific sound signals.”

In the monumental Mahorčič cave, part of the Škocjan cave system, guide Borut Lozej becomes a miniature figure in front of titanic limestone walls. Daylight streams through the natural portals, transforming the UNESCO World Heritage Site into a cathedral of light and shadow.

Then a beautiful collapse doline opens before us. Borut’s index finger draws an imaginary line: “From up there to the bottom the height difference is 154 metres.”

Soon after, the Thundering Cave swallows us

Soon after, the Thundering Cave swallows us. This gorge, which is considered Europe’s largest underground canyon, is the best-known part of the Škocjan caves.

Like a mountaineer in the Alps of the underworld, guide Borut Lozej stands on a rock in the underground Reka River. Further up, lights illuminate the visitor paths through Europe’s largest underground gorge.

Directly by the river we examine basins that have been shaped by millennia of water power and erosion. Then suddenly Borut stands on a rock in the middle of the Reka — like a mountaineer in the expanses of underground mountains.

The echo of our steps reverberates between the rock walls

The echo of our steps reverberates between the rock walls, accompanied by the eternal symphony of the River Reka. My thoughts are with the bold explorers and transform me from visitor to reverent pilgrim.

Between two sections of the Skojan Cave, my guide Borut Lozej (visible as a red dot) moves along a narrow path carved into the rock for visitors. A hundred years ago, visitors had to clamber along steel cables above the abyss towards the cave.

Deeply hidden beauties

My head torch light probes limestone walls whilst I navigate between bizarre stalactite curtains. An hour earlier I was received by four cave researchers: Vid Ursic, Jan Wahl, Kevin Klun and Primož Gnezda.

Stalactite spikes hang like petrified teeth from the ceiling

They equipped me and escorted me to Pivka Cave, one of the five entrances to the spectacular Postojna cave system.

Stalactite spikes hang like petrified teeth from the ceiling. Pivka Cave surprises with a variety of bizarre domes, passages and chambers that the five of us laboriously illuminate so I can photograph these dimensions.

From left to right: Primoz Gnezda, me, Jan Wahl, Kevin Klun, Vid Ursic.

Deeper in the cave a mirror-smooth lake doubles all stalactite formations and makes my guides appear like ferrymen in a hidden realm of stone and time.

“500 new ones are discovered annually.”

“Slovenia has more than 15,000 caves,” Kevin explains to me, “500 new ones are discovered annually. Everything longer than ten metres and large enough for humans to crawl through is designated as a cave.”

The Pivka Cave opens up before me like an underground ballroom. The mirror-smooth water doubles all the stalactite formations, and my guides appear to me like ferrymen in a realm of stone and time.

Postojna Cave is considered the world’s best-researched cave system. 117 species are at home here, even remains of hippos have been found.

The best-known cave dwellers are the famous olms

The best-known cave dwellers are the famous olms. These pale amphibians reach lengths of up to 35 centimetres. They can survive up to seven years without food and live to be 100 years old.

The olms in Postojna Cave can live up to 100 years (photo by Nik Jarh, Postojna Cave).

Slovenia’s national animal is blind and deathly pale. Formerly the region’s inhabitants believed they were the young of a dragon that lived in Postojna Cave.

This makes the olm the most fascinating inhabitant of the cave

An animal named Victor lost part of its rear right leg through the bite of a conspecific in March 2018. By August 2019 it had completely regrown and was functional. This regenerative ability also makes the olm the most fascinating inhabitant of the cave.

In Postojna Cave (photo by Iztok Medja, Postojna Cave).

As I wander through the passages of Pivka Cave towards the exit, I think of nature’s barely imaginable, million-year-long work.

The amazement has remained!

My exploration of Slovenia’s cave world ends here where it began in 1971 as an amazed five-year-old: in Postojna Cave, on my very first cave visit ever. Today, half a century later, I realise: the amazement has remained!

In the cathedral-like Postojna Cave, Annette walks amongst stalactites and stalagmites millions of years old – the 24-kilometre limestone cave is one of the world’s largest karst formations and has been open to tourists since 1819.

Slovenia, this small country between Alps and Adriatic, is a true treasure trove of nature — above as well as below ground. The three caves I visited showed me impressively: beneath the earth exists a second world, just as rich and fascinating as the other. Perhaps even more mysterious.

Read now:

The longest country in the world

Chile photo gallery

2 Min.In Valparaiso, we immerse ourselves in a vibrant culture that immediately captivates us. We then discover true natural beauty and breathtaking landscapes in Araucania. A truly contrasting journey.

Food for thought

Adventure is the salt in your life-soup

2 Min.Adventure is like salt in the soup of life. It adds flavour.

The pearl of Africa

Uganda – Tree lions and monkey shows

26 Min.Where do you find something like this: Mountains growing out of the rainforest? Lions that climb trees? And gorilla visits! Uganda is a sensation. The ‘Pearl of Africa’ surprises with unimagined natural abundance, an enormous variety of animals and friendly people.