Pubished in:

Germany’s largest nature travel magazine

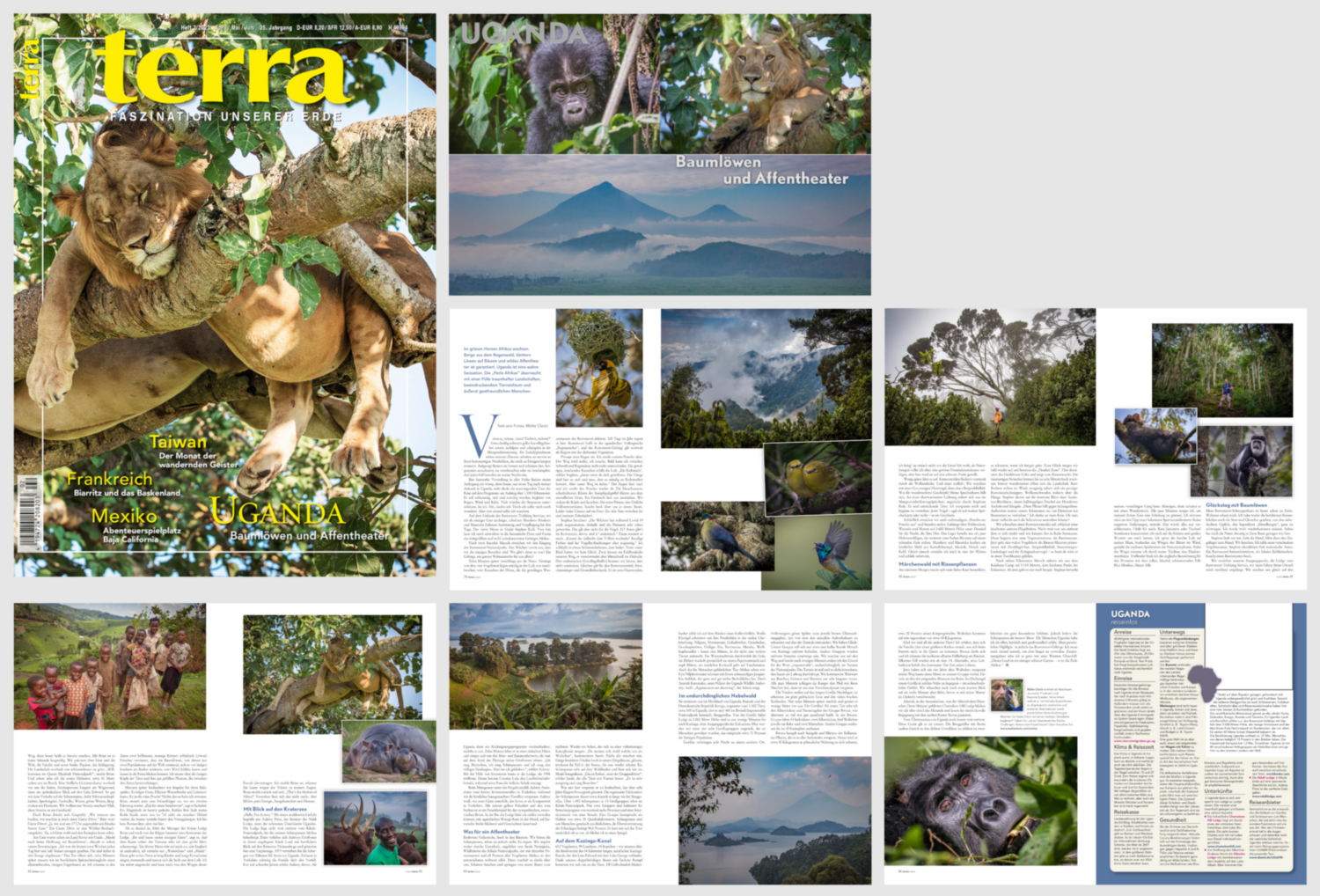

Coverstory | 12 Pages | Text & Photos

Tree lions and monkey shows

In the green heart of Africa, mountains grow out of the rainforest, lions climb trees and wild monkey shows are guaranteed. Uganda is a true sensation. The “Pearl of Africa” surprises with an abundance of dreamlike landscapes, an enormous variety of animals and extremely hospitable people.

Vriouuu, vriouuu, vizzz! Chwit, chwit!” About thirty black and yellow short-winged weavers clamor, chirp, and scold at dawn. In the eucalyptus tree next to my room, they nervously work on their cocoon-like nests that remind me of designer lamps. Fluttering around excitedly, they seem to cheer, scare, or scold their fellow birds.

It is expected to be muddy, steep and slippery, accompanied by rain, wind and cold.

And they do put an end to my night’s rest. Their loud performance early in the morning eases my excitement a little, because today, just one day after my arrival in Uganda, the most strenuous tour of the trip is on the agenda: an 1,150 meters climb up.

It is expected to be muddy, steep and slippery, accompanied by rain, wind and cold. Many would underestimate the strain, I read. ‘Really?’ I thought. Yet I was in for a surprise. But then first I should start hiking.

Emburara Farm, early morning: John Karuhanga (60) is closely connected to his Ankole-Watusis (cattle), he knows name, age and pedigree of each of the 45 animals.

On the premises of the Rwenzori Trekking Service, where I am staying as the only guest, Mumbere Modesto and Masereka Zalimon are shouldering equipment and food for three days. The fourth man is guide Stephen Kulé. I let him give me an introduction into the fantastic flora and fauna of the third largest and probably most unknown mountain range in Africa.

A mountain range, a whole world heritage site just for us?

After two hours of walking we reach the entrance of the Rwenzori National Park. The guard tells us that we are the only visitors. Where can you find something like that? A mountain range, a whole world heritage site just for us?

Ten minutes later, nature swallows us up. Songs of three or four species of birds are constantly in the air, interrupted only by the murmur of the rivers that drain the immense amount of water of the Rwenzori. It rains 320 days of the year here. Rwenzori means “rainmaker” in the Ugandan vernacular, and the Rwenzori Mountains are considered the region with the densest vegetation in the world.

The Rwenzori – one of the most fantastic landscapes I’ve ever walked through – while only walking through a very small part, mostly primary rainforest, like here. The picture shows scars from landslides. Permanent rain washes away the very steep terrain, and boulders pelt down the valley every day.

Rain promptly sets in. I put on my poncho.

The path becomes steeper, I gasp. Soon I can no longer distinguish between sweat and wetness from the rain. A tremendous, crashing roar fills the air. “A landslide,” Stephen explains, “you’ll get used to it. The slopes here are so steep and wet that landslides happen all the time. But our path is safe.”

The rain lets up and I take off the poncho again.

The soaking wet, scarlet flowers of the marsh splitgrass flash out of the endless greenery. A sound makes us pause. We crane our heads and listen. A first primate, an Eastern Full-bearded Meerkat, flits high above us in a tree. Unfortunately, no chance of a photo: too many branches between it and my telephoto lens.

“Poaching greatly increased during Covid-19, so the primates have become very shy.”

Stephen reports, “Poaching greatly increased during Covid-19, so the primates have become very shy. But this is not true for the birds. There are 217 species in the Rwenzori, 17 of which are endemic.”

Farewell from Uganda: A last view over the cultivated landscape with yam, tomato, bean and potato fields. In the background the Rwandan volcano Karisimbi (highest elevation) and to the right the Mikeno volcano (Congo).

Then he scrutinizes me. “Can you maybe change your T-shirt? Bright colors tend to be disadvantageous for bird watching.” I slip into something mud-colored, but alas: despite the new outfit, we are not lucky. A noble francolin crosses our path, but it disappears in a flash in the thicket.

We can hear the endemic Green-winged Bulbul, but cannot discover it. The same is true for the Ruwenzori’s Warbler, the Fern Cisticola and the Hermit Cuckoo. It’s really frustrating, I just can’t get them in front of the lens! I know, as a nature photographer, I should have a certain frustration tolerance, but here it is put to a severe test.

Every bird – whether on my memory card or not – is a gift.

A little later it clears up. Rays of sunlight flicker sporadically through the cloud cover. And then finally: we first spot a Gray-cheeked Hornbill, then a Mountain Bulbul.

What beautiful creatures! My memory card fills up. At an overgrown clearing, a pair of mangrove spectacled birds approaches us, attracted by Stephen’s calls. They are delightful animals. I relax and begin to understand: Every bird – whether on my memory card or not – is a gift.

Cloud-covered, deserted, nature-steeped – that’s how I experience the Rwenzori. Guide Stephen Kule comes from a village at the foot of the Rwenzori, he infects me with his obsession for mountains – and especially birds.

Finally, after repeated “poncho on, poncho off” and hours of steep climbing over boulders, roots and mud, we reach our domicile for the night, the Sine Hut, at 2,600 meters. The camp consists of a few wooden huts scattered under tall trees on a narrow ridge.

Mumbere and Masereka cook a delicious meal of mashed potatoes, cassava, meat and cabbage. Immediately afterwards, I retire to one of the huts and fall asleep.

Fairy tale forest with giant plants

The next morning i feel my left knee, going downhill it hurts. Fortunately, we soon climb up again and enter the “Heather Zone”. Here the Ericeae Erica dominates and tends to grow to giant proportions: the tree-like shrubs can grow up to eight meters high.

“This plant helps against snakebites. Also, our shamans use it to drive demons out of possessed people.”

The landscape opens up ever more wondrously. Beard lichens blow in the wind, a curious cute Ruwenzori flycatcher approaches me, cloud swaths waft over the slopes. Stephen points to the fiery red blossom of a Scadoxus blood flower, a hemispherical tuft of hundreds of spines and stems: “This plant helps against snakebites. Also, our shamans use it to drive demons out of possessed people.”

I am thinking of my knee. I wonder if it could be used to drive out the pain, too.

In three days, only once I had a clear view of the Rwenzori Double-Collared Sunbird, one of 17 endemic bird species of Rwenzori.

We startle a ruwenzoriturako, catch sight of its bright red lower wing feathers. Not far from us it settles down and we can marvel at it in peace.

Then a new vegetation zone begins, the bamboo zone.

Now a real bird show takes place: within minutes cinnamon-winged starling, mountain bulbul, brown-cheeked warbler and the king sunbird present themselves – as colorful as if they had fallen into an ink box.

After a seven kilometers hike, we approach Kalalama Camp at 3,153 meters, the highest point of the excursion. From now on it’s all downhill. Stephen notices my cautious gait as we descend, then cuts me a walking stick.

Near the path, through my telephoto lens, I spot a Blue Monkey.

Every few minutes I stop to give my left knee a rest. I remember a tip from a well-known sports mental trainer: no negative comments, ever. That would only make things worse.

For me it means no complaining or cursing!

Instead, I concentrate on the small and big wonders around me. I feel the humid air on my skin, watch the swaying of the leaves in the wind, enjoy the endless play of nature’s symphony. Near the path, through my telephoto lens, I spot a Blue Monkey.

High up in a tree in Kibale National Park, this chimpanzee enjoys the first rays of sunshine after a downpour.

I find the name for the primate with the noble, bluish shimmering fur most appropriate.

Lucky day with tree lions

My Rwenzori introduction course already ends today. Wistfulness comes over me. I have seen neither the famous giant lobelia nor the lakes and glaciers, not to mention the ice-covered peaks, the legendary “Moon Mountains”. I guess I will have to come back. Rarely has nature captivated me as it does here.

Stephen walks in front of me, raises his hand, then brings his index finger to his mouth. We listen. I count nine different bird calls, Stephen identifies five endemic species. A Rwenzori sun squirrel, a local squirrel, scurries up a tree trunk.

We arrive at our starting point, the lodge run by Ruwenzori Trekking Service, where my driver Brian Owach greets me, beaming. We set off right away, because today we have to cover a lot of ground. Being with Brian it is not boring for a second. We chat about God and the world, the family and our passion, drums.

“We have to hurry, we’re doing another game drive.”

The landscape changes from muddy brown to green. “Welcome to Queen Elizabeth National Park!” beams Brian.

And immediately I see the first elephants, about 50 meters away in the bush. A southern green monkey changes sides in front of us, anubis baboons loiter by the side of the road, then a spectacular view of Lake Edward.

Almost no traffic on the gravel road, but black-headed lapwing, sparrowhawk, osprey, monitor lizard, green expanses, mountain ridges on the horizon. We just wanted to gain miles? Well, this track is a present!

Queen Elizabeth National Park is one of the few places in the world where lions climb trees during the day. This male lion briefly interrupts his sleep, glances at me, and dozes off again a few moments later.

But Brian steps on the gas: “We have to hurry, we’re doing another game drive.” Sorry? Game drive? “Yes, we’re announced for 5 p.m. at the Ishasha Sector Gate.” A game drive is a wildlife viewing trip.

Well, I guess I should have read the itinerary.

A Land Rover with guide is already waiting at the gate. “Don’t get your hopes up for tree lions,” he immediately dampens our expectations. “I’ve been here every day for the last two weeks and haven’t seen a single one. I’m sure they took off for the Congo.” The gate opens, and ten minutes later, in the most glorious late afternoon light, we head for a solitary, giant fig tree. I spot two light brown, massive bodies in the branches: sleeping lions!

Brian now heads for a rocky cliff where a second vehicle is waiting. “Time for a sundowner,” he says with a smile.

Researchers assume that the tree lions, of which only two populations exist in the world, protect themselves in that way from pesky insects on the ground, are cooled down by the breeze and can better peer into the distance. I marvel at the animals’ huge heads and their well-filled bellies hanging down between the branches.

Minutes later we observe impalas playing courtship games. Wildebeest, elliptical waterbuck and lyre antelope follow. It is pure splendor! I wasn’t expecting any of this.

Brian now heads for a rocky cliff where a second vehicle is waiting. “Time for a sundowner,” he says with a smile.

A folding table is already set. Cool beer runs down my throat, a single elephant passes down below in the valley, the sun sinks behind the Virunga Mountains. I’m not a romantic, but this.…

Evening atmosphere at Lake Mutanda.

As darkness falls, the manager of Enjojo Lodge leads Brian and me down from the cliff to the lodge’s restaurant. “You’re my only guests today,” he says. On the lawn next to the patio, I see a large crowd. An older man approaches me, his English is slurred, I only understand “orphanage” and “music.”

Then it commences: about eighty children and young adults sing, drum and dance their hearts out. It is contagious and let myself be carried away by the waves of this joy. I beam at Brian, hardly recognizing him because of the tears in my eyes.

Once upon a time, Aubrey’s grandfather fell in love with this remote piece of land with magnificent views of Nyinambuga Crater Lake and established a tea plantation here.

Brian beams back and exclaims, “That’s the rhythm of Africa!” I can’t understand it anymore, but I can feel it: pure energy, exuberance and ecstasy.

Overlooking the crater lake

“Hello, I’m Aubrey.” With a beaming smile, Aubrey Price, the owner of Ndali Lodge, one of Uganda’s most beautiful accommodations, greets us.

The lodge is not far from Kibale National Park, home to most of the chimpanzees in Africa. Once upon a time, Aubrey’s grandfather fell in love with this remote piece of land with magnificent views of Nyinambuga Crater Lake and established a tea plantation here. In 1973, dictator Idi Amin’s henchmen drove him out of Uganda. At home in Yorkshire, the family kept silent about the incident.

One of the highlights of any trip to Uganda: A visit to the mountain gorillas in the Bwindi Impenetrable Forest. Only a second after this shot, the six-month-old baby gorilla disappears out of sight in the shade of a bush.

It wasn’t until he was eighteen that Aubrey learned about it. Then, when Uganda adopted a reversion program, he relocated. For ten months, he lived in a simple hut and came to an agreement with the maize and banana farmers who now lived on the site of his grandfather’s plantation. “I like people, I like chimpanzees, and I like the complete fresh start. So I stayed,” Aubrey explains.

With the help of investors, he built the lodge, which opened in 1996. Today, cousin Lulu oversees the farming operation, while his wife manages the local school.

At lunch under the pergola, Aubrey shares anecdotes from the last investor meeting in Yorkshire as we devour the delicious homemade tortellini.

I could have lingered endlessly in the lodge’s bar, Ugandan Waragi rum in hand, staring at historical engravings and hearken to stories.

Aubrey knows how to entertain guests, something he learned as an innkeeper in Yorkshire. With his yellow polo shirt and pink socks, he is a perfect example of the likeable, eccentric Brit. I could have lingered endlessly in the lodge’s bar, Ugandan Waragi rum in hand, staring at historical engravings and hearken to stories.

What a monkey show

Distant screeching, high up in the trees. We hear the chimpanzees, but do not see them. It is raining. We trudge on through the undergrowth, led by Sarah Nemigisha, game warden of Kibale National Park, one of the most diverse in the world with thirteen primate species and eleven percent of all bird species in Africa.

Then there’s a rustling right above us, shadows darting and leaping from one tree to the next. Another cry, rising to a many-voiced cacophony. “There must be some fighting over a female,” Sarah comments. Not all join the kerfuffle.

In the middle of the tea growing area of Uganda. At almost every photo stop I am quickly surrounded by curious and friendly children.

Some nibble fruit high up in a hackberry tree, yawn, dry their fur in the sun, which is now shining again. A chimpanzee rests on the forest floor, having his picture taken like a model. “This is Enfuzi , one of the group leaders,” explains Sarah, who knows all the animals by name. “He is very curious and likes visitors.”

What we are privileged to observe here has taken over eight years of acclimation. The so-called habituation of chimpanzees takes about twice as long as that of mountain gorillas.

Over 1,450 chimpanzees in 13 large groups live in Kibale National Park. Only two groups are habituated for visitor groups of no more than six and an interaction time of one hour. One group occupies a habitat of about 35 square kilometers.

We also see Africa’s most dangerous animal for humans: a mother hippo cuddles with her cute young.

Chimpanzees are genetically most similar to us humans, with a 98.8 percent genetic match. Indeed, on the tour I often felt as if I were looking into a mirror.

On the Kazinga Channel

612 bird species, 95 terrestrial animals, 34 reptiles – we are amazed at the biodiversity of the 34 kilometer long natural Kazinga Channel, which connects Lake Edward with Lake George.

Thanks to our double-decker, flat-hulled boat, we get close to the animals. I count eleven yellow-billed oxpeckers on the back of a Cape buffalo. White kingfishers buzz around their nest cavities in the steep bank. Egyptian goose, glutton, goliath heron, gray kingfisher, gray-headed gull, sacred ibis, cormorant, marabou, bald eagle – hardly a minute goes by without another species appearing.

A warthog rummages through the earth, an elephant leisurely totters to a papyrus bush and plucks leaves, a stately crocodile dives down.

Mother and baby hippo on the banks of the Kazinga Channel. Individual animals weigh up to 4,500 kilograms. 5,000 hippos roam the waters that connect Lake George and Lake Edward. It is the world’s largest population of hippos.

We also see Africa’s most dangerous animal for humans: a mother hippo cuddles with her cute young.

A sight that is not at all threatening. But Azariah Kamerako, our guide from the Uganda Wildlife Authority, knows: “Appearances can be deceiving”.

In the impenetrable cloud forest

They live only in the highlands of Uganda, Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo, a total of about 1,100 animals, about 535 in Uganda, of which 460 are native to the Bwindi Impenetrable National Park: mountain gorillas. From the Gorilla Safari Lodge at an altitude of 2,000 meters it is only a few minutes to Rushaga, the starting point of the excursion. Here we will be assigned to one of the eight gorilla groups that have been habituated to humans, representing about 70 percent of the local population.

The terrain is steep and so densely overgrown that hardly any draft comes through.

Gorillas spend each night in a different place.

Early in the morning, scouts go to the last place where the gorillas spent the night in order to find out where they are and to report this to the headquarters.

We are lucky: our group will only need about half an hour’s march starting from Rushaga. Other groups will need several hours of trekking.

We set off and it’s already after a few minutes that I surmise the reason for the word “impenetrable” in the name of the national park. The terrain is steep and so densely overgrown that hardly any draft comes through. We make very slow progress in the tangle of bushes, grasses and trees.

Every few minutes the rangers clear the path with their machetes, then we are granted a breather.

The trackers come across the latest gorilla night camp, identifiable by trampled grass and the many fresh heaps of excrement. Only ten minutes later there is a rustling and grunting just a few meters in front of us. The gorillas!

A look I will never forget: The serene elemental power of a silverback – nothing can compare to it.

The first animal I see is the silverback and eponym of the group, Bweza, which translates as handsome. The Bweza group consists of 15 individuals: two silverbacks, five females each with a baby and two males. Other groups include up to 40 individuals.

Bweza moves hand over hand for stems and leaves of Brillantaisia plant, which he calmly eats. Today, he will eat about 30 kilograms of plant fare, about 20 percent of his body weight. Females have a daily intake of about 18 kilograms.

And where are all the other animals? I am being told that the family spreads out over a larger area so as not to get in each other’s way while feeding. Bweza turns and I recognize the distinctive silver fur colouring on his back.

Silver fur only starts to grow from the age of 14, and the dominant animal retains its leadership function throughout its life.

To meet a gorilla at such close range in the jungle – an indescribable feeling.

Now a four-year-old female is relaxedly making her way barely a meter past our group. For many, this is the most defining moment of the trip. To meet a gorilla at such close range in the jungle – an indescribable feeling. We also catch a glimpse of a six-month-old baby before it disappears into the thicket with its mother.

In the evening, at the awesome Chameleon Hill Lodge, run by the lively German Doris Meixner, we all look out over Lake Mutanda and chat about our impressive encounter with the gentle giants.

Uganda is still far away from overtourism.

We should make use of this favourable situation. To experience the mountain gorillas. with their gentle disposition. in those dense jungles is without a doubt a very special experience. However, the chimpanzees put on a better show.

I have found the people of Uganda as open, warm and hospitable. My personal highlight, however, is the Rwenzori Mountains. I must go back again to spend more time there. In a nutshell, I see it quite like once Winston Churchill: “This country is one beautiful garden – it is the pearl of Africa.”

Order TERRA MAGAZINE here (only in German):

Print and digital edition

Read now:

Ranger Training in South Africa

Something is up in the bush

16 Min. Exploring the wilderness on foot in the midst of lions, elephants and buffalo? You can learn to do that. In summer 2019, I will join a field guide course in South Africa.

Interview with South African ranger legend

“Wilderness and nature have made me who I am today.”

8 Min. Bruce Lawson has worked as a field guide / wilderness warden since 1992 and has over 18,500 hours of logged wilderness experience. He is one of the most impressive people I have met in my life. Here is my interview with him.

Ranger training on the edge of the Kruger National Park

South Africa photo gallery

< 1 Min. Exploring the wilderness on foot in the midst of lions, elephants and buffalo? You can learn to do that. In summer 2019, I will join a field guide course in South Africa.