Published in:

Germany’s biggest nature travel magazine

14 pages| text & photographs

Ice climbing – a marginal phenomenon

Ice climbing is a marginal phenomenon in Nuuksio National Park. In fact in the truest sense of the word, as there is a popular ski slope right next to the ice slope. First, Annette and I swap our hiking boots for hard-soled rental boots, from which the crampons attached underneath cannot fall off. We put on our harness and helmet. With our legs apart so that the crampon spikes don’t dig into our trousers, it takes us a few minutes to plod to the access point.

Climbing guide Marja attaches the safety rope to the harness with a double snap hook. The rope runs to about twenty metres above us through a bolt at the head of the rock and then down to Marja, who secures us.

Some of the ice axe blows are like a small ice blast

“Put the ice axe far above you,” she instructs us. “First on the right side, one, two times, then left. Pull to test if the ice holds. Then pull up. Hips against the wall. Legs shoulder-width apart. Step your feet horizontally into the ice, not too high, not too low. Find your footing. Secure your stance by rocking. Look up. And repeat.”

It’s more strenuous than it sounds. We cannot put trust in the ice axes and crampons at first. After all, our weight is hanging on just a few thin steel spikes. But the fun of the climb and the dopamine rush quickly drive away the initial physical and mental strain. Some of the ice axe blows are like a small ice blast. Our helmets with visors defy the small ice avalanches.

Annette ice climbing.

After arriving back at the bottom drenched in sweat, I want to know why Marja is fascinated with ice climbing. “I listen to the sound of the ice when I hit it. You climb with your ears. The vibration of the ice also tells you a lot. You have to be particularly careful on long ice passages and extended surfaces. For me, ice is softer, livelier and more talkative than rock. And every winter it shows itself in a new guise. I like that.”

Reflective materials and signal colours increase visibility

Icebreakers and breakthroughs in the harbour

“This thing has a catch. And it can save lives.” Leif Rosas is Managing Director of RedRib Experience in Helsinki and shows Annette and me a handle with a claw. “Imagine you’ve just broken through the ice. No one is there to help you. You have to pull yourself out of the water. Without an ice hook like this, it can be very difficult. As you’ll soon find out for yourself.” Annette and I exchange a puzzled look. Leif smiles. He knows the punch line: “Don’t worry, you’ll put on one of my survival suits first.”

Ten minutes later, two red Teletubbies stagger anxiously across the ice in Helsinki’s harbour area, not far from Kaivopuisto Park. Leif encourages us to jump into the water. “Don’t worry,” he calls from the shore, “you’ll stay warm and dry.” And indeed, after diving in, not a drop penetrates the suit.

There is no sign of the ice breaking in. You sink completely into the water in a matter of a second.

Survival suits like this are a life insurance policy for ship personnel in emergencies. The surface material neoprene, a synthetic rubber, insulates and keeps the wearer warm, even over many hours in cold water. Polyurethane-coated nylon forms a further water-repellent layer and keeps the suit durable. The inner lining consists of a layer of heat-retaining foam. Reflective materials and signal colours increase visibility.

Leif reports: “A Chinese man once fell asleep in the water. And thanks to the suit, an extremely water-shy Frenchman managed to take his first ever dip in the sea.” I hadn’t thought of such helpful aspects. The next order from Leif reaches us: “Try to pull yourself onto the ice over there.” Not so easy. As soon as I approach the ice, it breaks away from underneath me in large floes. I struggle to paddle towards the new edge of the ice, heaving my upper body onto the surface.

Crack, I break through

Now I could do with an ice claw. My neoprene fingers have no grip. Only wild foot paddling pushes me forwards a little. I break in again. Next attempt. This time I turn in with my shoulder and try to place as many parts of my body as possible evenly on the ice. I roll onto the ice with my arms outstretched and lie on my back. I’ve done it! As soon as I stand up, Leif calls me back to the edge of the ice. Step by step, I tentatively slide forwards. Then I realise that the surface of the ice is bending in front of me. Only minimally. Crack, I break through. Much more unexpected and faster than I thought. Without warning. Without the increasing creaking or cracking that you hear in films. But well, now I know my predetermined breaking point.

I finally manage to crawl out of the water onto the ice again. I spread my weight over as much of the ice as possible so as not to collapse again.

Ultimate: Diving under ice

Excuse me? Three and a half hours? Is that how long our welcome sauna ceremony is supposedly to have taken? Ten people look at each other, puzzled, smiling and shaking their heads that they have forgotten time or at least estimated it differently.

Leigh Ewin stands at the end of the table and is amused by the reaction of his guests. Born in Australia, he has lived in Finland for several years and is an expert in breathing techniques, freediving, ice swimming and cold exposure. His seminar on freediving under ice, which began three and a half hours ago, is unique in the world.

Each of the four sauna cycles ended with an ice bath in the frozen lake

And it started quite differently than expected. A Finnish shaman greeted and sang to the participants in the sauna, whipping volunteers with birch branches. The birch branch travelled from hand to hand. Everyone was invited to reveal something about themselves as a child, adolescent, adult and also about dying. A spiritual exercise like this can, if you allow it, create a sense of security, openness and healing. Each of the four sauna cycles ended with an ice bath in the frozen lake – to then enter the next symbolic phase of life respectively sauna, feeling as clean and reborn as possible.

Three and a half hours. That’s a sauna record for everyone sitting around the long table, exhausted, hungry but dopamine-shaken: a professional boxer and fitness trainer, an Israeli crypto investor, two entrepreneurs from Paris and Shanghai, a German cold coach, a British banker, his two sons, a Finnish woman called Heidi and my wife Annette and me.

First short ice bath in the frozen lake. Many more will follow.

Oki serves the food: “This is Hereford Tenderloin, the favourite cut of beef for many people because it has the most tender meat. To be precise,” he runs his index finger along a fillet, “this is the psoas major muscle, the large loin muscle that sits just below the sirloin.”

This is followed by bowls of potatoes, carrots and onions – coated in a glaze of butter, thyme and honey.

“And of course,” continues Oki, “Saaristolaisleipa! The bread of the islanders in south-west Finland. Very dark in colour. Slightly sweet. A special rye malt speciality. Enjoy the flavour.“

I am woken by a strange noise

While twelve people in the snow-covered wooden hut called ‘Villa Paratiisi’, somewhere a two hours’ drive from Espoo, wash down the delicious evening meal with lingonberry water while chattering animatedly, a veiled crescent moon rises far above them in the deep black Finnish night.

Breath less

I am woken by a strange noise, look through the small window and catch sight of Oki. He is standing on the frozen lake just a few metres from the shore, cutting large slabs of ice out of the lake with a two-metre-long rough ice saw. The result: a triangular pool that could hold three deer.

Oki saws a triangular pool free. It freezes over again in just one hour.

Before solving the pool riddle, we submit to some breathing exercises. After all, we should store enough air in our lungs for free diving under the ice and acquire a relaxed, controlled state of mind, known as a ‘mindset’.

Course-developer and leader Leigh Ewin introduces us to the Wim Hof breathing technique, developed by Dutch ‘Ice Man’ Wim Hof, who offered prove for the health-promoting aspects of cold showers and ice baths in many studies. He also immortalised himself in the Guinness Book with over twenty world records, including the record for the longest ice bath at 1:53 hours.

I feel a pleasant dizziness

The Wim Hof method consists of several breathing cycles of thirty breaths each. Lying comfortably on the floor, you inhale very deeply into the diaphragm and then relax or simply release the completely full lungs – without actively forcing the air out of the lungs. This enriches the oxygen in the blood. The breathing rate increases with each cycle. At the end of a 30-breath cycle, you take a maximum deep breath. Then Leigh instructs: “Empty lungs”, whereupon the air leaves the lungs without active intervention. Then hold your breath. Relax. At some point, countdown from ten. Breathe in. Next cycle. Increase breathing speed. At some point I forget the time. The pauses to hold my breath are marvellous. I feel a pleasant dizziness. For some others it’s more extreme: tingling all over the body, hallucinatory patches of colour. And how long did we end up holding our breath? Leigh reveals: Three minutes. With empty lungs. Unbelievable.

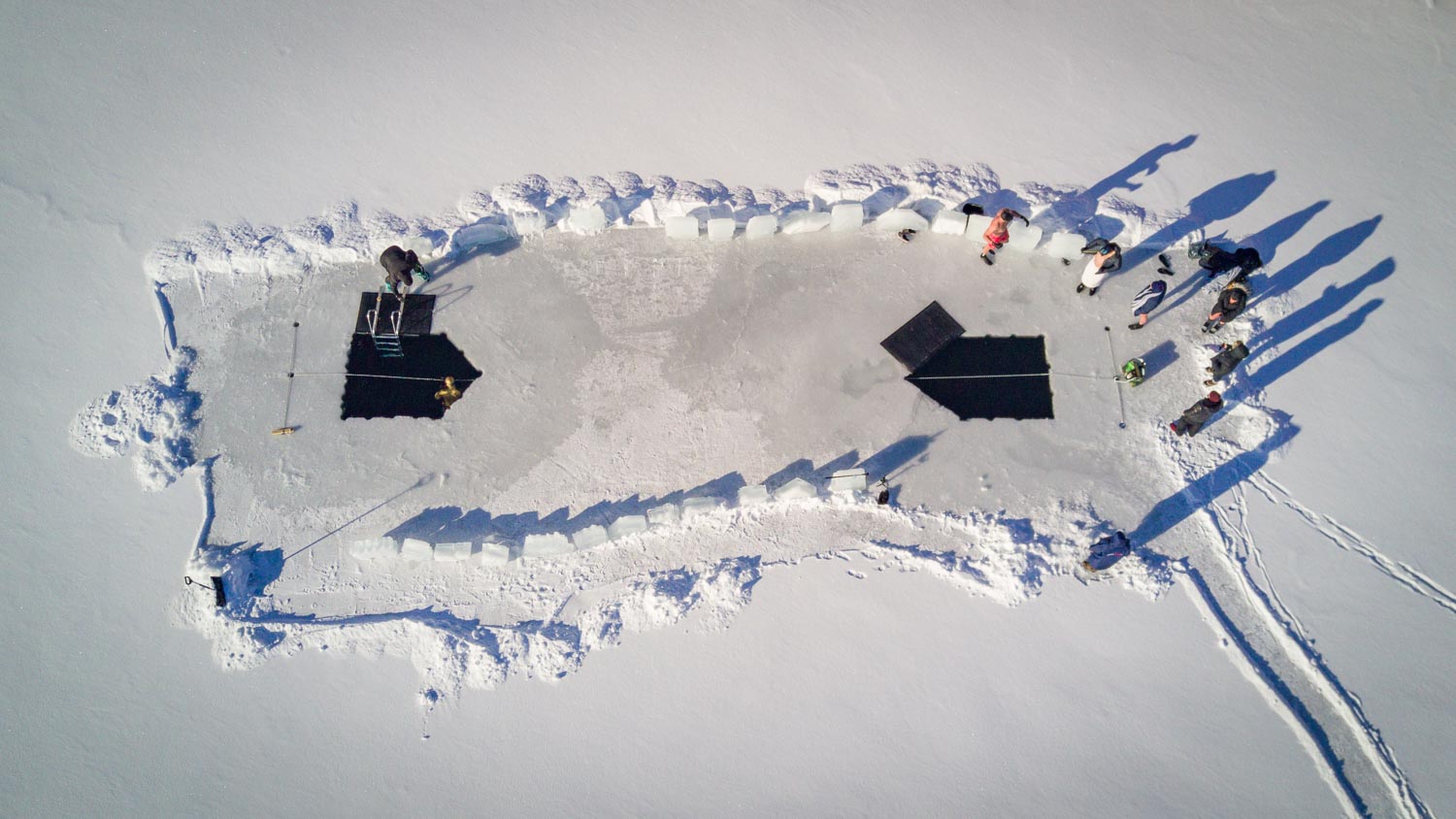

The seminar location about two hours’ drive from Espoo. The two ice baths can be seen in the foreground.

During the break, I talk to Daniel, the cold coach from Berlin. As an architect, he suffered a burnout twice before ‘the ice’ and the breathing technique brought him back to life. “Our bodies are made for the cold. Thousands of generations before us shivered in icy winters, crossed waters, starved for months. Countless such metabolic winters have made our bodies very resilient. Today, we hardly utilise this anymore.” Daniel believes that the comfort zone is the new danger zone. Many modern illnesses can be traced back to a physical under-demand and overeating.

Daniel is almost unstoppable. Leigh joins him. Experts among themselves.

Daniel continues: “A three-minute ice bath won’t kill anyone. Instead, it increases the release of serotonin, melatonin, testosterone and dopamine – up to 300 per cent in some people. The inflammatory markers, i.e. inflammatory pathogens, are significantly reduced after just three minutes in an ice bath over five days. This has all been proven in studies.” Daniel is almost unstoppable. Leigh joins him. Experts among themselves. An expert dialogue about the latest scientific findings begins: Vasodilation, brown adipose tissue, neuropeptide Y, theta brainwaves, I can’t keep up.

After the ice bath, we go one better: Rolling around in the snow.

And how did Leigh come up with ‘this crazy ice story’, I want to know.

“Years ago, I worked as an intern in Espoo. My colleagues lured me into an ice bath with their mobile phones out. Avantouinti, which translates as ‘dipping into a hole in the ice’, has long been a tradition in Finland. After a few moments, I escaped from the water screaming. My colleagues laughed, shared the videos and commented: “Look, our intern. He loves the cold!”

The embarrassment resumed the next winter. But this time Leigh was armed with white socks. Which reduced the slipping on ice, but it didn’t extend the time in the ice. Laughter again. Shared videos again.

After many attempts, he was able to stay in the cold water longer and longer

Leigh vowed not to let that happen again. He would prepare for the next time. Three bus stops before his office, he got off, warmed up with countless push-ups before jumping into the ice and tore his foot open to bleeding. He didn’t give up and after many attempts, he was able to stay in the cold water longer and longer.

At the next Christmas party, no mobile phones lit up and nobody laughed.

Encouraged by his self-efficacy, Leigh explored breathing techniques, trained with Wim Hof, learnt to free dive, experimented with meditation, yoga and biohacking until he started offering seminars himself. Two years ago, this culminated in the idea of teaching what he considers to be the most intense and challenging way to experience the cold: freediving under ice.

Seven minutes of humming in an ice bath. This stimulates the vagus nerve, which in turn slows down the heartbeat.

Down the hole

The temperature is just below zero degrees. There is no wind. In our bathing suits, we trod in single file to the ice hole in the frozen lake, twenty metres from the hut.

Under Leigh’s close supervision and guidance, we all slide into the water one by one. The first time you dive in, your head stays above water. After a warm-up phase in the sauna, the second immersion takes place, now with diving goggles. The head dips into the water for a few seconds. The third immersion is then carried out with a snorkel. Everyone can now take as much time as they like to look around underwater in peace. The aim is to gain as many underwater sensory impressions as possible so that we are familiar with them the next day.

There is no driving licence that teaches us how to use it

Breathe the way you want to live

In the heat of the sauna, the German breathing and cold trainer Daniel Ruppert turns up the heat: “We breathe around 20 – 25,000 times a day. Breathing is by far the most frequently used, life-sustaining function in humans. Without food we can survive for perhaps 3 weeks, without breathing not even 10 minutes. We learn nothing about it at school. There is no driving licence that teaches us how to use it.” During long stays abroad, including months in a Shaolin monastery, Daniel came into contact with breathing techniques.

Group photo with course leader Leigh Ewin (front).

„Breathe the way you want to live, said one of my Shaolin masters. You can breathe yourself awake, breathe yourself calm, breathe yourself warm, cool down. Breathing is just crazy shit!” laughs the fifty-two-year-old. One of his coachees, professional boxer Moritz, calls over: “Watch out, he’s proselytising you!” Daniel nods calmly, smiles and continues: “We usually breathe too much, too quickly. Stress is caused almost exclusively by an increased breathing rate. And it disappears with controlled, calm breathing. We only need up to five breaths per minute. Eight is mild stress, twelve is significant stress and anything over fourteen breaths is chronic stress. We have 375 million years of evolution to thank for the fact that we are allowed to breathe at all! There must be something exciting in it. We just have to find out.”

The humming stimulates the vagus nerve

No sooner have I digested Daniel’s knowledge than my head is spinning from Leigh’s scientific pressure cooking: the influence of breathing and cold on energy and hormone production, blood chemistry, digestion, body temperature regulation, the lymphatic system, emotion regulation and the autonomic nervous system. Phew, I think I really need to cool down now!

Seven minutes of humming

Now the triangular pool comes into play. Oki removes the ice that has formed on the surface since this morning. We get in in teams of three, each in a corner. We remain in the ice humming for seven minutes. The humming stimulates the vagus nerve. This in turn strengthens communication between the brain, stomach and heart, reduces the heartbeat and allows us to stay in the ice for longer.

Aerial view of the entry and exit points.

Now hold your breath

At the end of the day, Leigh makes us do one last breath-holding exercise. Eyes are closed. Our bodies are wrapped in warm clothing, either lying or sitting, so that no cold impulse can distract us. Two minutes to go until we stop breathing. Then countdown. And hold your breath! After a while, my diaphragm makes itself felt. The pressure increases. Until I can’t stand it any longer. One minute thirty. Heidi, the Finn, manages three minutes! How does she do that? I find holding my breath extremely uncomfortable, it’s not my thing at all. Recovery time until the next stop: Just one minute. OK, pull yourself together! Ffffffffffhht! … Two minutes flat. Heidi increases to 3:30.

Leigh is thrilled: “Great job, guys!”. He raises his index finger: “Don’t worry. Each of you has four to five times as much air available as you will need for tomorrow‘s dive.“

Miro stands before us in an extravagant golden full-body drysuit

In the Taivassalo quarry

Leigh has already told us about Miro Suonpera, who is monitoring and filming our dives today in the frozen quarry lake near Taivassalo. The Finnish record holder dives almost 100 metres under the ice with just one breath. Now he stands before us in an extravagant golden full-body drysuit, customised by his sponsor. His name is emblazoned on the back in large letters. Thanks to Miro, the abandoned quarry now has the makings of a James Bond film set.

Daniel is ready to dive in and signals the OK sign to safety diver Miro.

There’s nobody here but us. A tiny sauna tent for a maximum of three people is steaming at the edge of the frozen water, and about 50 metres away on the lake is the diving site.

We take off our winter clothes. In addition to the swimwear, diving socks, gloves and swim caps insulate sensitive parts of the body. I’m fourth in line. Leigh waves me over and I step forward. He attaches the safety belt to me. This is loosely connected by a rope to the safety line, which in turn runs from the entry hole to the exit hole. That way nobody gets lost or drifts off.

I couldn’t really enjoy the trip

I sit down on the edge, my legs dangling in the water. One last relaxation, focus, OK sign for Miro and off I go: I dive in, grab the white safety line and, looking up, pull myself towards the exit, about a metre below the ice cover. After 17 seconds, my head pops out of the water. I couldn’t really enjoy the trip, I was far too anxious to get out again quickly. But there’s one more lap.

Farewell group photo after each of the ten participants completed at least two free dives under the ice.

The second time I take it slower. Underwater, I take a break a few metres before the exit. My legs are floating upwards. I press my soles against the ice and look vertically into the depths. Wait. Look around you. Take it in like this. Not easy for me as a photographer without tools. I gaze into this strange world, capturing the light, which changes abruptly from the icy white of the surface to the turquoise-dark green of the water and darkens smoothly towards the bottom. It clicks and bubbles in my ears. Small air bubbles rise to the surface of the ice and wander around as if looking for a way out.

It could hardly be colder. It couldn’t be better.

As soon as I emerge from the water, Leigh motivates me to dive again. So let’s do it a third time. Less than half a minute later, I leave the ice – and sway like a drunk. “Brain freeze,” laughs Leigh, “your brain is missing blood. It’s still inside your body, where it keeps your heart warm.” Fortunately, the spook is over after a few seconds. The dive, however, is something no one will easily forget. It could hardly be colder. It couldn’t be better. Off I am to the sauna tent.

Read now:

Pure inspiration

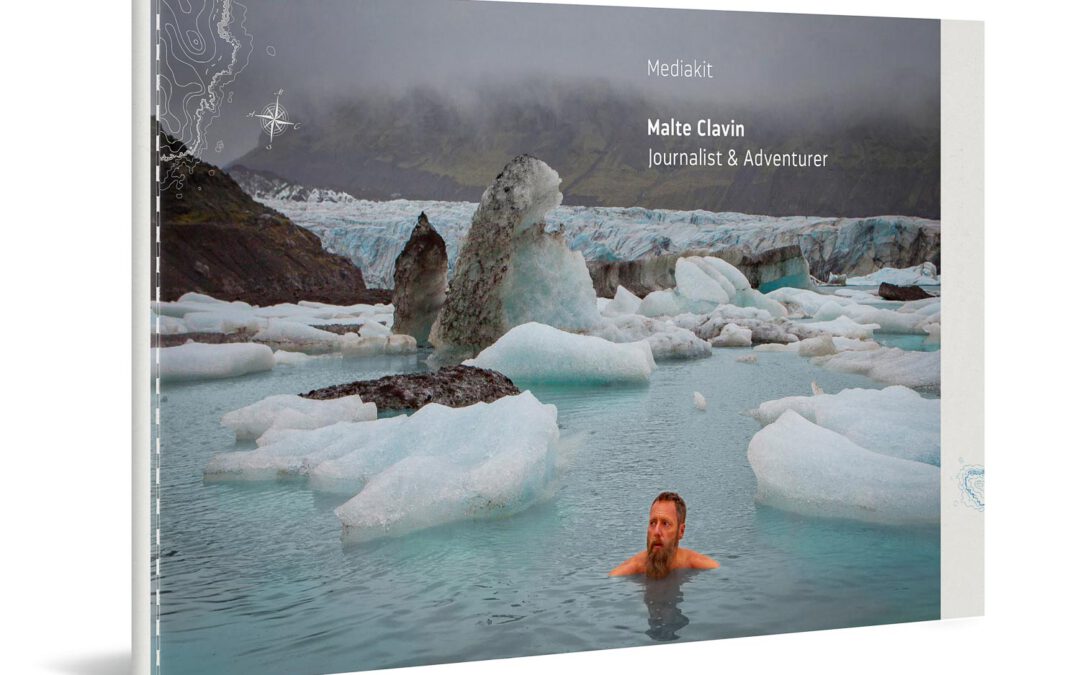

My new media kit 2025

< 1 Min.In this brand new 28-page media kit, I show you my work as an adventure journalist and speaker: Expeditions, travels, challenges – everything that excites me. Let yourself be inspired.

Extreme activities in winter

Finland photo gallery

2 Min.Attention: Extreme! Under-ice-diving-in-Badebüx. Plus pictures of ice climbing and ice breaking from wintry Finland.