Published in:

![]()

Germany’s third-largest national daily newspaper

Reach: 769,000 readers

In the flickering light of the slowly dying campfire, the shadow of the poisonous sting on the scorpion’s tail makes it seem larger than it is. Still, this is no small fellow. Attracted by the light and heat of the flames, a curious ten-centimetre-long body crawls across half-decayed leaves of the jungle floor beneath my hammock.

The nocturnal creatures of the jungle seem to be gathering now for a campfire party. I’m no arachnid expert, but the hairy buddy of that sting creature now trotting by, looks an awful lot like a tarantula. Although they are not dangerous to humans, I wonder whether its extremely venomous nephew, Phoneutria nigriventer from the Brazilian wandering spider family, is also lurking somewhere. Because instead of spinning webs, they prefer to search the jungle floor for food.

All around us there is cooing, whistling, screaming, roaring and knocking.

The male cicadas are the shrillest. To impress females, they roar louder than a motorbike at over ninety decibels. Add to this a tree frog concert and a symphony of rustling and rattling leaves and the cacophony is complete. Welcome to our Brazilian night camp.

Here in the Amazon, the jungle is wild, untamed, a thriving organism in which everything seems to be connected. Here, man is not the ruler, but a visitor. Humbleness seems appropriate, caution advised. Anyone who thinks they can just walk in here is risking body and soul. There is a wide range of illustrious ways to die in the rainforest.

It is considered the eccentric climax of the rubber baron era.

Manaus

It seems centuries since we left Manaus, the capital of Amazonas, the largest of Brazil’s 26 states, the day before yesterday. By comparison: the Amazonas state is as big as France, Germany and Spain together. Germany fits into it 4.4 times. Nevertheless, the area is sparsely populated, only four million people live here, half of them in Manaus. During the rubber boom from around 1880, the city became very wealthy. When the price of rubber dropped significantly from 1910 onwards, the city fell into decline.

Manaus looks unreal. A mega-city full of ugly, mould-infested concrete behemoths with a few surviving jewels from its heyday. Like the neoclassical opera house ‘Teatro Amazonas’ from 1896, considered the eccentric climax of the rubber baron era. Much of the building material was imported, including marble from Carrara in Italy.

What a location for a city of millions: in the middle of the humid jungle, on the banks of the Rio Negt and the Rio Solimões, which join to form the Amazon not far from Manaus. A spectacle called ‘Encontro das Águas’, Portuguese for ‘confluence of the waters’. Here, over a width of six kilometres, the warm blue-black water of the Rio Negro merges with the cooler sand-coloured water of the Rio Solimões.

If you want to travel to Manaus, it is best to do so by plane or boat. The road network is dilapidated. Often the roads are overgrown or completely washed away during the rainy season. Besides, the distances are enormous. The distance from Rio de Janeiro to Manaus is over 4,300 kilometres. The same as the linear distance from Berlin to the North Pole.

Manaus is our stopover on the way to Vanessa Marino and Leo Principe, about 140 kilometres north of Manaus in the municipality of Presidente Figueiredo. Vanessa, originally from Venezuela, and the French-Italian conservationist and photographer Leo bought over 270 hectares of land here a few years ago.

They built their house there, where they live with their three children and Vanessa’s mother. And they also built a guest house on the site. With their company ‘Amazon Emotions’, they receive visitors in a small setting and acquaint them with the beauty of the rainforest. The welcome is so warm and cordial that I immediately feel like a friend of the family and not like a paying guest.

Lungs of the earth

From the veranda of the guest house, lying in my hammock, I look out over primary rainforest. I close my eyes – no easy feat for me, the image-obsessed photographer. I count the sounds in the jungle panorama. When I reach ten, I give up. I hear spotted guans, which the Brazilians have named after the sounds they make: Aracuã. Howler monkeys start from the left, then a parrot screams and other birds and insects unknown to me.

The roof of the jungle colours purple from the flowers shining through the white wafts of mist. Scents of fresh rot, earth, heat and humus fill my nose. The smell of fertility. It is almost unreal, this view over the purple trees, this sight of an untouched planet.

Leo Principe lost his heart to the Amazon and everything that lives and thrives there forty years ago. “In 1989, I was the captain of a luxury sailing yacht. We sailed the Amazon for a while. I was overwhelmed by the beauty of nature and decided to return,” says Leo.

“Four months later, the time had come. I had an appointment with INPA (note: Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazonia, the National Amazon Research Institute). It was about a photo assignment on river dolphins in the Amazon. I flew from Barbados to Manaus, looked out the window and couldn’t take my eyes off the green sea of trees. And so I stayed.”

60 % percent of the Amazon’s biodiversity is found in the treetops.

In the following decades, Leo documented large parts of the flora and fauna of the Amazon. He published his work in picture books and international magazines. 60 % percent of the Amazon’s biodiversity is found in the treetops. Leo developed a non-invasive technique to climb the forest giants of the rainforest and take photographs up there.

His goal: to make people aware of the abundance of this area, which is not called the green lungs of the earth for nothing.

“After I got together with Vanessa in 1998, we travelled around Brazil in a camper van for a year,” Leo says. A trip that led to a new chapter in their lives. “We wanted to learn more about ecological building, clean energy, sustainable ways of interacting with the jungle. Conservation is a philosophy of life for us.

All the knowledge we have gathered and implemented in our country, we want to pass on to our children and our guests. “Leo and Vanessa teach their children Geo (18), Kinan (17) and Kena (12) themselves, but only when they actively request it. Most of the time, the children choose how they spend their day. This seems to work wonderfully. Geo is now learning Japanese, his fifth language.

Black earth

Leo is fascinated by the agricultural techniques of ancient civilisations, especially Terra Preta. “Terra Preta is a very fertile black soil that covers ten percent of the Amazon basin”, Leo says, on the small field where he is trying to reproduce this artificial soil.

“This soil is very fertile and hardly leaches. People have been using it here for over two and a half thousand years. You make it by producing charcoal from certain plants and then mix it with the existing soil. ” Terra Preta acts like a water- and nutrient-containing sponge: it fosters the formation of microorganisms and the release of humus substances. This ensures a long-term supply of nutrients to the soil.

Leo is also researching other traces of forgotten civilisations. He shows me aerial photographs in which large circles appear. “We found out what these circles were: huge fish ponds. I am pretty sure that the Indians dug these fish ponds, they were clearly created by humans.

Around the ponds were several species of fruit-bearing trees like açaí and lupuna. They were selected to produce fruit all year round. Since the trees were by the water, the fruits fell into the pond. Food for the fish. All year round. Without the Indians having to do anything themselves. Ingenious, isn’t it? “. Leo taps the ground with his index finger. “I want to build a pond like that here on our land.”

A sharp flash shoots through my head, tears fill my eyes.

Cavity cleaning

“Do you want to try?”Leo beckons me and hands me a kind of bamboo straw with two ends. He opens a small box and takes out a brown powder with his thumb and forefinger. “This is what the Indians use to clean their cavities“ he explains with a finger pointing to his nose and a mischievous smile. “Let me show you.”

Leo rubs the powder into one end of the stalk and then puts it in his mouth. The other end he inserts into one of his nostrils. Then he blows. Leo’s face contorts. Now he hands me the bamboo straw. I feed the straw with powder and blow it into my nose. A sharp flash shoots through my head, tears fill my eyes.

“Good, now blow your nose.” Afterwards, my head is drastically empty, feeling twice as big and I am able to smell everything three times as intensely. “In the jungle you need all your senses,” Leo explains, “a blocked nose can be a handicap. With this secret recipe you solve the problem. “

Leo’s words run through my head as we later hike through the rainforest looking for a good place to camp for the night. Guide Samuel shows us the way. With his machete he occasionally cuts down plants that block our way. Suddenly he stops and raises his palm. Slowly, almost ominously, he moves his head in all directions and sniffs the air.

He whispers, “Can you smell it?” I sniff the air too, but get no further than damp earth, rotting plants and pollen from tropical flowers. Samuel nods in a northerly direction. I point my nose in the same direction with no idea what he is actually trying to tell me. Then he whispers: “Jaguar”.

Suddenly I am as awake as after the powder nose shot. I look around. Jaguars have the habit of jumping on their prey from behind in order to incapacitate the victim with just one bite in its skull. Just yesterday, Samuel told me that a member of his family had been attacked and carried off by the nocturnal hunter.

Jaguar against man

I hear something rustling and flinch. But Samuel relaxes and from his conduct I infer that danger probably has passed. “When my family member disappeared, we didn’t try to kill the jaguar out of revenge.”, he tells me. “So we killed a wild boar and a capybara and offered them to the jaguar – in exchange for the bones of our relative. We respect the jaguar. In the jungle, he is king.”

Samuel lifts his machete, cuts a branch and holds the cut-off part with his thumb on the tip. “Open your mouth” he invites my companion Cathy. To everyone’s amazement, he pours cool liquid into her mouth.

Samuel explains that the branch is actually the liquid-storing root of a type of kapok tree. “You have to know where to cut”, he explains, “in the right place you don’t damage the tree and in just a week a new branch will sprout. If you know the jungle well, you never have to go hungry or thirsty.”

We return to our base camp. Only a few hours before, this was an empty plain. Now we are standing in the middle of a fully functional jungle camp. The remaining part of our group, together with Vanessa, Leo and their children, have hung hammocks between ipé trees and provided each mat with a natural rain canopy made of two layers of huge philodendron leaves.

A barbecue table made of wooden stakes picked up from the jungle floor sits enthroned in the centre of the camp. An orange fire glows beneath it. Two huge tambaqui fish are roasting on the table. Samuel hands out palm leaves as plates and wooden spoons he has just cut out of fallen branches.

Cheeky monkeys

My travelling companions sleep in their hammocks, I doze and observe the vigilant Samuel. An hour ago we were, with great relish, still dining on the two tambaqui. The tambaqui is a very fat fish that – Leo presumes – probably lived in the old fish ponds. It feeds on nuts and tree fruits that grow along the Amazon River. Have I ever eaten more delicious fish? I can’t recall.

“These little beasts have sharp teeth with which they will go after your throat.”

Samuel’s powerful lamp illuminates the treetops. There is a rustling up there. I am curious and climb out of my hammock, make sure I don’t step on any scorpions or other animals and approach Samuel. What is happening up there? “Night monkeys,” he whispers, “I use the light to keep them at a distance. They are curious and are attracted by the fire. A larger group might even attack us. These little beasts have sharp teeth with which they will go after your throat.” I wait for an impish smile, exposing the last phrase as a joke. In vain.

I stare into the dark foliage and see nothing. My torch doesn’t help either. My untrained senses can’t pick up subtle, jungle-specific movements and sounds like Samuel can. I give up, say goodnight and nestle myself into my hammock. With Samuel on guard and supported by the swinging of my hammock, I drift off into the realm of dreams

Hanging out in the treetop of creation

Our hike back to the ‘Amazon Emotions’ lodge takes about two hours. There we rinse off the jungle dirt in the outdoor showers and then devour an energy charge for the next capriole: mango juice and bowls of fresh açai, a mixture of muesli, cuia squash and bananas, topped with dried slices of coconut.

Equipped with helmet, climbing harness and gloves, I stand in front of a 50-metre tall jungle giant, a tree called ‘Angelim ferro’ (lat. Dinizia excelsa). This species of tree of hardwood or ironwood is sought after in the timber industry, it is considered to be very durable. Carpenters use the wood to make high-quality furniture.

And now we’re supposed to go up there? “Yes,” Leo nods, “the view at the top is fantastic. So let’s go.” He has already harnessed me to one of the endless red long ropes hanging like vines from the treetop. A second rope, about 1.40 metres long – with a handle at the top and a step bar at the bottom – connects me to the long rope. I’m supposed to use this to pull myself up on my own?

What follows is a workout that’s a riot: a one-arm pull-up with a simultaneous one-legged knee bend, in what feels like endless repetition. After only a few metres of elevation gain I have to take a break. I gasp, my pulse drums, sweat drips into my eyes. Around me it is airless, humid and thirty degrees. Breathe deeply. Keep going. An hour later I am at the top. The water bottle is long empty, my trousers and T-shirt soaking wet with sweat. Exhaustion gives way to a touch of pride.

I plump down into a hammock that Leo has hung up here. The gentle white-haired man was the last to start and the first to reach the top. Exhaustion is not in evidence on the professional arborist – the official name for tree climbers. Like a gibbon, he clambers between branches, guests and hammocks. Just amazing.

The view over the rainforest canopy is magnificent. The sun beams orange backlight through the foliage. A fish toucan flies by, searching for insects and fruit in the treetops. Its garishly coloured beak, almost four times as big as its head, is perfect for this.

Below me, the jungle floor slowly disappears in the shadows of darkness. The volume of the soundtrack of nocturnal animal noises increases. I humbly appreciate the thick branches that carry my fellow climbers and me up here. Only when the sun has completely disappeared do we rappel back down to solid ground.

Tips und Information

Getting there: Usually KLM/Gol Air or LATAM Airlines fly to Manaus (via São Paulo or Rio de Janeiro).

Travel time: Rain falls all year round in the Amazon basin, but only for one to two hours a day in the dry season. Best time to travel: June to October.

Jungle tours: Amazon Emotions offers multi-day adventure packages with jungle trekking and survival training, three days from approximately 470,- euros, www.amazonemotions.com. Tours with a private guide with the option of sleeping out in the open are offered by www.brasilienwege.de

Information: www.braziltour.com

Read now:

Pure inspiration

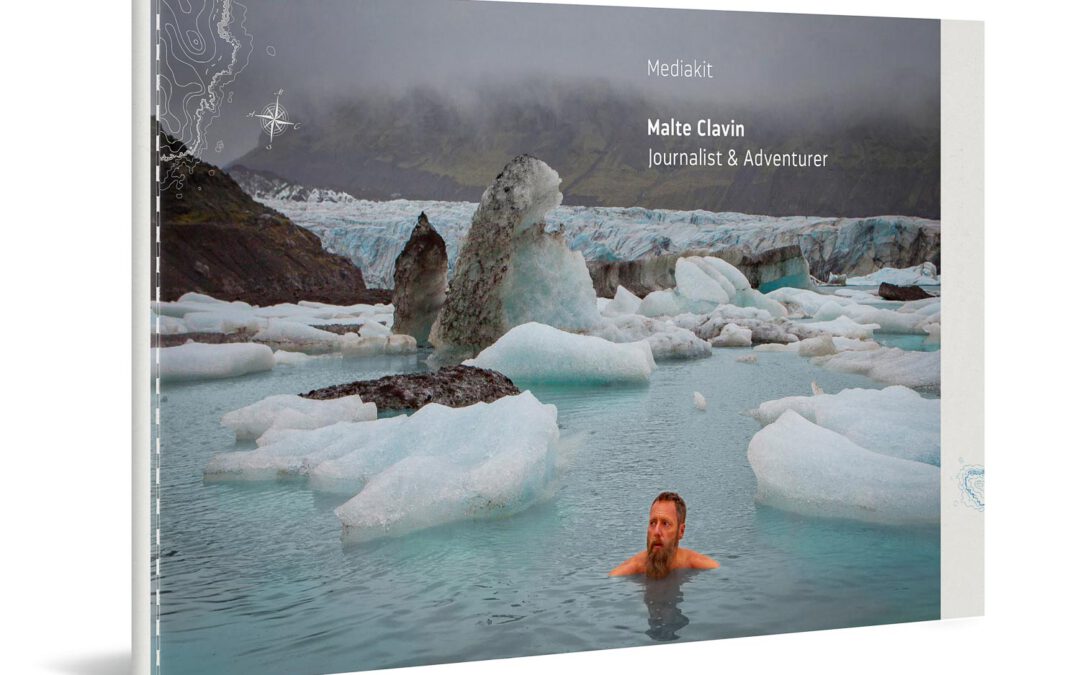

My new media kit 2025

< 1 Min.In this brand new 28-page media kit, I show you my work as an adventure journalist and speaker: Expeditions, travels, challenges – everything that excites me. Let yourself be inspired.

Expedition to the "green lungs" of Brazil

Amazon – Up the jungle giant

17 Min.Deep in the Amazon is a place where, surrounded by the wilderness and all its inhabitants, you can experience the rainforest in an extraordinary way. I went on a voyage of discovery here.

A voyage of discovery in the Amazon

Brasil photo gallery

< 1 Min.Expedition into the depths of the Amazon region with all its inhabitants. I was in the middle of it with a small group and couldn’t get out of my amazement.