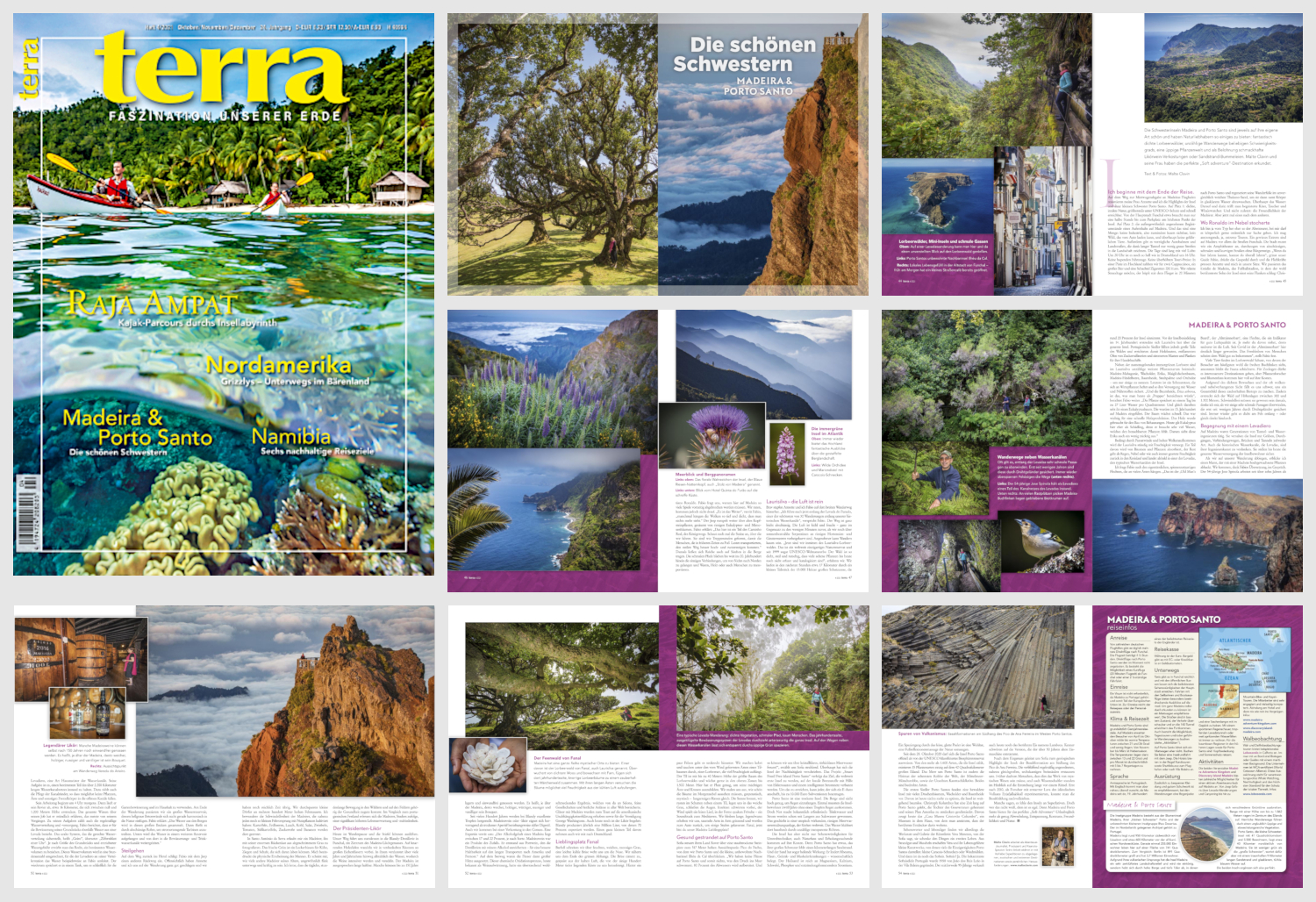

Published in:

Germany’s largest nature travel magazine

14 Pages | Text & Photos

On the way to the car rental drop-off at Madeira’s airport, my wife Annette and I look back at the highlights of the island and its little sister Porto Santo: in first place: dense, healthy nature, mostly under UNESCO protection and quickly accessible: from the capital Funchal we need 28 minutes to the parking lot at the highest point of the island. Second is not a place, but that which makes travelling in Madeira so pleasant. And that is a lot: no industry, at least hardly visible. No game that may jump in front of the car, in general: no dangerous animals. Intact motorways and country roads that, thanks to the long tunnels only appear as a few grey lines in the landscape. No discernable social hotspots. Long days with intense light: at 8 pm it is still bright like in Germany at 4 pm. No honking. No rip-offs: in a pub in the highlands of Madeira we paid €7,50 for 2 cappuccinos, 1 big beer and a pack of cigarettes.

No game that may jump in front of the car, in general: no dangerous animals.

Where Ronaldo poked through the fog

I’m more of an adventure guy, so I need to get down and dirty. Physically. I will go for arduous, even the extreme. The streets of Funchal are a different extreme. The city seems like an amphitheatre, criss-crossed with sloping, narrow and winding streets with no sidewalks. “If you can drive here, you can drive anywhere” beams our Guido Fabio as he presses down on the accelerator. Road bumps and centrifugal forces press Annette and me into our seats.

Fabio asks us what we think is the reason that so many matches here must be halted prematurely.

The jeep rumbles on over ancient cobblestones, the road lined only by giant eucalyptus and mimosa trees. Fabio explains, “This is part of the ‘Caminho real’, the ‘King’s Path’. Look at the stones we’re driving over. They’re shaped like steps so that the people, who carried loads back then, could climb up and down the steep path more easily.” Back then also, rich people had themselves carried up the mountains on palanquins. Until well into the 20th century these narrow paths remained the only links to get from the south to the north and to transport goods, timber and also people.

View of the northeast coast from the Vereda do Arieiro hiking route.

Obediently Annette and I trudge after Fabio on the wide hiking trail. “I will now lead you along the Levada do Furado, one of the most beautiful of 30 hikes along our historic water channels” Fabio promises. It’s only slightly downhill as we continue. It is cool and damp – in contrast to the few minutes before, when we were still winding our way along sunlit serpentines past extensive seas of hydrangea and gorse. Hiking could hardly be more pleasant. “Now we’re in the middle of the Laurisilva laurel forest. This is a unique nature reserve and has even been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1999. The forest is so dense, steep and slippery that many rare plants have not yet been recorded and catalogued. Over the next few hours, we walk about 17 kilometres through a small section of the 15,000-hectare protected area, which takes up 20 percent of the island.

The forest is so dense, steep and slippery that many rare plants have not yet been recorded and catalogued.

“And the tree heath, Erica arborea, is what we would now call a ‘prepper”

Many animals find shelter in the laurel forest, of which the visitor probably sees the cheeky, fat chaffinch most often, otherwise the fauna is reticent. There are probably more interesting destinations for zoologists, but botanists and flower fans can roam here to their hearts’ content.

“Since Covid, the Old Man’s Beard has grown longer”, Fabio is pleased to observe.

Channel clogging: encounter with a levadiero

Madeira has created generations of tunnel and water engineers. They honeycombed the island with ditches, cuttings, passages, bridges and tunnels of every imaginable length. The historic water channels of Madeira, the levadas, are also the result of this art of engineering. Even today the levadas still provide the entire water supply for the islanders.

At the next bend during our hike, I spot a man chopping down tall plants with a machete. Aided by Fabio’s translations, we strike up a conversation. Jose Spinola, 54, has been working as a levadiero for over 10 years, a kind of caretaker of the water channels. His job is to keep a certain part of the over 2,200 kilometre long water channel network in good shape. This includes maintaining the edges of the channels so that no plants, branches or other foreign material falls into the open channels.

The ancient system called ‘Geiro’, translated as ‘clock face’, ensures the equitable distribution of water.

On the way back to the hotel Fabio takes another way back with the jeep. Obviously, Annette and I did quite well on the hike and we still have plenty of time left. We pass by small villages settled under many hundred meters high rock walls. I admire the lack of fear of heights of the Madeirans, who have cultivated almost every little rocky outcrop with agricultural crops: potatoes, strawberries, leeks, cabbage, lettuce, onions, tomatoes, sweet potatoes, sugar cane and bananas are harvested there.

His working day starts at 4 a.m., he then checks his preserve, about 16 kilometres long, ranging from sea level to 1,200 meters up.

Today we take a break; the hiking boots can air properly. Our goal is to the Blandy Distillery in the centre of Funchal, an epicentre of Madeira liqueur indulgence. On creaking wooden floorboards we sneak past large oak barrels in darkened rooms. Water gradually evaporates in them over many years and even decades, intensifying and refining the wines. Madeira has an exceptionally long shelf life. Some can be stored and enjoyed perfectly well for up to 150 years. It is said that the older the Madeira, the softer, woodier, spicier, nuttier and more vanilla its bouquet.

Madeira wine was a product of chance.

Then at sea the barrels were exposed to intense heat. This chemical oxidation process, known today as wine warming, had a surprisingly palatable result, which from then on contributed to salons, fine parties and occasions all over the world. Glasses filled with Madeira were raised to toast the American Declaration of Independence as well as for George Washington’s swearing-in. Today, the liqueur is still in demand: Blandy produces a million litres a year, 70% of which is exported. A tiny part of it we take back with us to Germany.

Barefoot I walk over damp, soft mossy grass; a light cool breeze touches my nose. I approach the end of the green slope. The breeze picks up, fed by the cold air coming up from the coast a few hundred meters below. Behind a few rocks, the descent is vertical, and I turn back, diving under the skewed branches of a til, a laurel tree that collects much of the moisture.

The til is the largest tree in the laurel forest, reaching up to 40 metres in height, and likes to grow in the upper zones up to 1,500 metres. Here it has room enough to form mighty branches and canopies. I imagine how beautiful the trees look in the morning mist, ghostly, mystical, like long-armed giants.

Fanal, you are my favourite spot here on Madeira now.

Sofia guides her Land Rover along a bone-dry rocky track to the 517-metre-high vantage point of Pico do Facho, from which we overlook Porto Santo and the small uninhabited neighbouring island of Ilhéu da Cal. “We have no rivers. And therefore nothing to flush out filth into the sea. 80 percent of the wastewater is treated. And so we are happy…” now Sofia’s face brightens, “… with a crystal clear, turquoise blue sea!” In general, the island is committed to sustainability. The “Smart Fossil Free Island Porto Santo” project is dedicated to becoming the world’s first island to banish fossil fuels using electric cars and a smart grid. To this end, purchases of e-cars are subsidised with up to 10,000 Euros.

At one point, the islanders had to go twelve years without a drop of rain.

But the island doesn’t have attractions for environmental engineers only, nature fans and those looking for relaxation get their share also. Porto Santo has something that its big sister lacks: a sandy beach. That even has healing properties. It has been scientifically proven to alleviate rheumatism, skin, joint and muscle ailments. The healing sand is rich in magnesium, calcium, sulphur, phosphorus and anti-inflammatory strontium. A walk through the fine, smooth powder is a treat for our feet, a do-it-yourself foot reflexology massage lasting for up to nine kilometres.

The first settlers of Porto Santo found a forested island with many dragon trees, junipers and tree heath. There is no sign of this today, the island is largely treeless, if not bare. Christopher Columbus lived on Porto Santo for a while, married the governor’s daughter and devised his plan to discover America. The “Casa Museu Cristovão Columbo”, a museum in the house where the explorer is believed to have lived, still bears witness to this.

Now 95 years old, he still sells the famous ice cream called Lambeca.

Some say the islands lack superlatives. For those unaware of that, they couldn’t care less. Because Madeira and Porto Santo offer more than enough variety, relaxation, contrasts, friendliness and nature for the perfect soft adventure holiday bliss.

Order TERRA MAGAZINE here (only in German):

Print and digital edition

Read now:

Fifty Shades of Green

Madeira photo gallery

< 1 Min.The sister islands of Madeira and Porto Santo are each beautiful in their own way and have much to offer nature lovers: fantastically dense laurel forests, countless hiking trails of all difficulty levels and lush flora.

Colourful eco-paradise

Costa Rica photo gallery

< 1 Min.Shortly before the 2nd lockdown, I take the opportunity for a short escape to Costa Rica. In almost deserted national parks, an exuberant plant and animal world awaits me. A detailed article on my trip will appear in Terra magazine in April 2021.

A Piece of France in the South Seas

New Caledonia – South Sea with sunken forest and mangrove heart

19 Min.Like a South Seas dream come true, New Caledonia lies east of Australia in the Pacific Ocean. Seen from Europe, this is actually directly at the other end of the world. Those who take the long journey will experience turquoise water and dazzling white beaches as well as many surprises.